This is a re-post. This article was published February 2020. I’m going to re-publish articles from my extensive blog as I think many of them are still relevant.

This article deals with using Aperture Priority along with grads to work out your best exposures. I’m aware that many use manual, but if you read below, you may see why I think AP is a good mode to work in.

—

Each year I get participants using Manual mode for almost everything they do. Today I’d like to cover why for me I would tend to use Aperture priority (along with exposure compensation) for most of my work. The only caveat about this is that when you get into very low light situations, most cameras prefer to work in Manual. They somehow fail to be able to give sensible readings in AE.

My main reason for using Aperture Priority above anything else is mainly due to this:

‘when using grads along side aperture-priority,

the camera automatically re-balances the exposure’

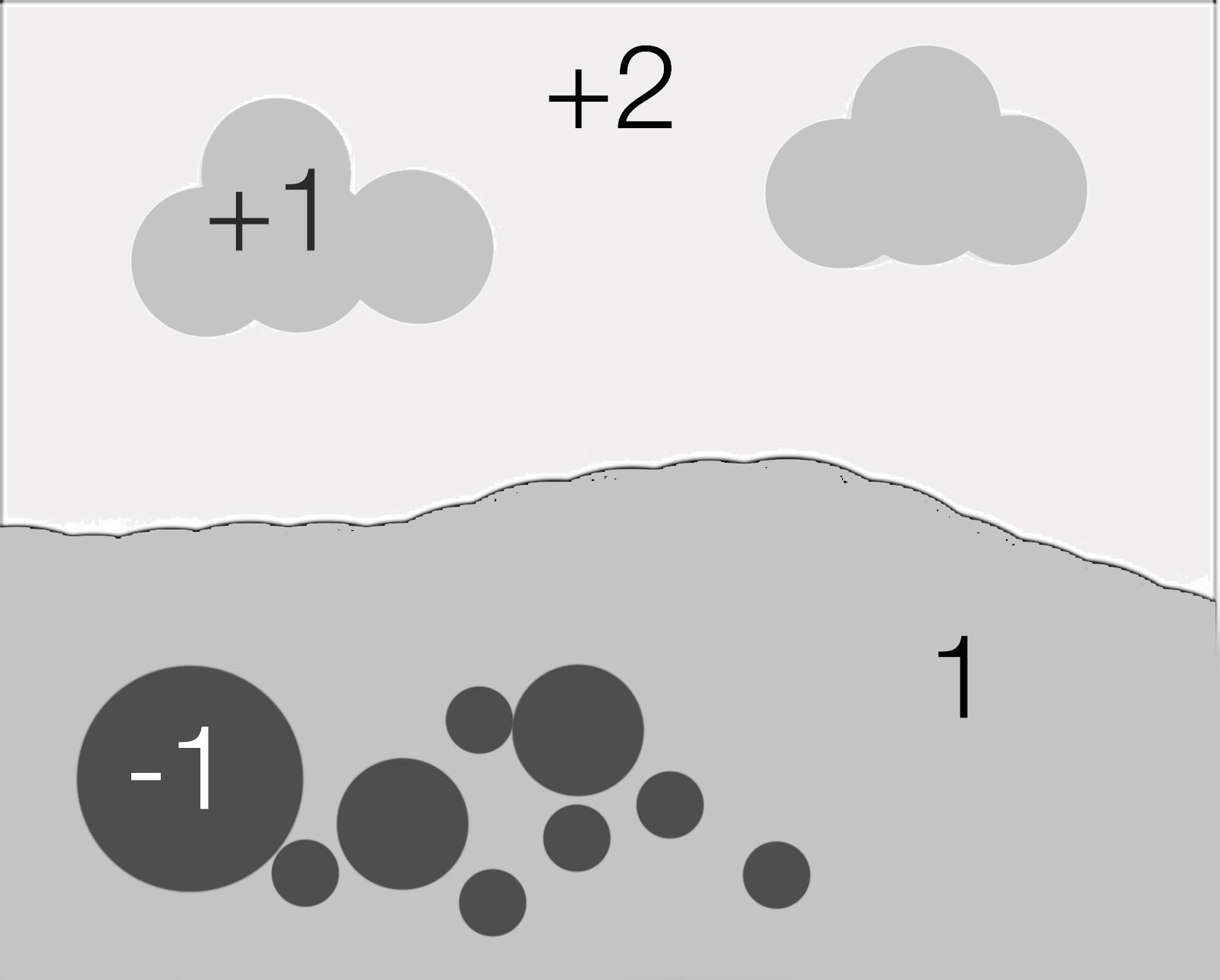

Consider the diagram below. On the left I show how the exposure of sky (blue) and ground (green) are worked out. Bear in mind that the light meter inside your camera just sums up all the tonal differences and takes an average (if you’re not clear on metering, see the previous article Light meters are dumb, they just try to turn everything 18% Grey).

The main point about this diagram is:

Before applying a grad, the camera just has to take an average between sky and ground. So the ground is underexposed and the sky is over exposed.

When applying the correct strength of grad, the sky gets darker (as we have been taught - this is what grads do - they darken the sky). But something else happens as well………

The ‘something else that happen as well’ is this:

The ground gets lighter.

Why is this? Well if you study the diagram, and think about it for a little bit, you can quickly see that if you apply a grad, the difference in stops between the sky and ground is reduced. Since the camera’s light meter is looking for an average, the new mid-point is much less further away from the sky and ground tones. In other words, the contrast range has been reduced and the light meter just picks a new average between the new light and dark tones.

When working in Aperture priority, the average exposure is being computed in real time. You can even see it adjusting the mid-point exposure as you push a dark grad down on the frame. As you do so, the ground gets lighter, because the difference between sky and ground is reduced.

This doesn’t happen in Manual. You don’t give the camera a chance to automatically re-balance the exposure for you.

Manual isn’t always the way to go

For me, I would shoot in Aperture Priority for most of my work. I’d prefer to do this because each time I apply a grad, the camera just recomputes, and works out the new average meter reading for the scene.

Before I am shot to bits by people declaring that I think Manual mode is bad. I’d like to make very clear that Manual still has its place. Often times when working in very low light, most cameras give up metering in Aperture priority, and so I have to resort to using Manual for these times.

It’s just that in Manual, you don’t see the ground lifting up in value when applying the grads. So I prefer to use Aperture Priority when I can.

Aperture Priority + Exposure Compensation

If it were me, all cameras would be designed to have just these three elements:

Aperture Priority

Exposure Compensation

Manual mode

Because most of the time, aperture priority with a bit of exposure compensation is all that’s required. Sometimes I need to go longer than 30 seconds, or need to set up the camera is very low light, so I’ll resort to Manual.

Grads are still valid

If you’re a digital shooter that believes you don’t need grads, I’d like to urge you to think again. There are many benefits of working with grads:

As pointed out above, when you use a grad to darken the sky, you also lift the tonal values in the ground.

You get more shadow information in the ground

The negative you come home with is more pleasing to work with. It requires less effort in processing to figure out if it’s any good to begin with

Working with nicely exposed negatives is much more inspiring that working with negatives that need a lot of massaging in post.

Are you really going to process ALL of your digital files to see if they turned out well? I doubt it. How can you tell if the image is any good when the sky is bleached out and the ground is muddy?

For me, points 1, 2 and 4 are perhaps the most important for me.