When you take the horizon away from a landscape photograph, the viewer is inclined to invent one.

We tend to imagine what we need to complete (to make sense of) what we see. This is true of photography, but it is also true of how we use our visual cortex in our daily activities.

Everything we see is a ‘construction’, and it’s so innate to us that we’re not even aware of it.

Consider the Necker cube. You immediately know it’s a wire frame cube. But what is interesting to me is that our ‘construction’ can be influenced. You can choose which walls of the cube become the back wall and the front wall. After a while you can flip them so what was the back wall is now the front wall, and what was the front wall is now the back wall. The necker cube is great at illustrating that your vision is a ‘construction’.

Necker cube. Can you imagine this cube in different ways?

When we look at photographs, we ‘imagine’ the scene in our mind’s eye. We essentially construct it. And most interestingly to me, we tend to create any missing supporting elements we need to help us make sense of an image. This means that we may imagine things that aren’t actually there.

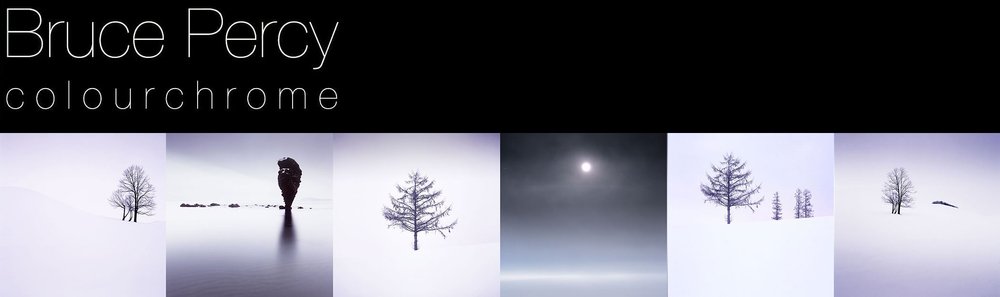

In the three photographs in this post today there are no horizons in the shot. Yet I think most viewers of these three photographs will ‘imagine’ a horizon. They will essentially imagine what isn’t there to help them complete (or make sense of) the image.

There are many ways in which we tend to ‘imagine’ what isn’t there. For example:

What is outside of the frame. We tend to ‘continue’ the photograph outside of the frame. In our mind’s eye we tend to imagine beyond the perimeters of the frame.

Objects at the end of the frame tend to continue outside of the frame. If a mountain begins to slop up and out of the frame, we tend to imagine the rising angle continuing outside of the frame.

If there is no real horizon, we either tend to invent one in our mind’s eye, or if there is something within the photograph that can act as a substitute, we will use that. This is what false horizons are.

Knowing about this ‘feature’ of the visual cortex to ‘fill in the gaps’ can be a great photographic tool.

Indeed, in the case of point 1. above, (we imagine what is outside of the frame). I tend to use this a lot to help viewers imagine that the landscape is very empty. If there is nothing around the perimeter of the frame then one tends to imagine that everything outside of the frame is a continuation of that ‘nothingness’.

So in today’s post, I’ve selected three of my images where there isn’t a clear horizon. You can ‘imagine’ where the horizon is, even though in some of the images there really isn’t a horizon. No really, there really is absolutely no horizon in one of the images in this set. Do you know which one?

Imperceptable horizon, Lençois Maranhenses. The horizon does exist. Except that I’ve chosen to edit it to make it ‘almost’ invisible.

In the above image, perhaps, depending on your monitor, the horizon is perceptible. It is there, but it’s so faint that it’s almost become invisible.

Deliberately making things imperceptible

Indeed, this was my intention during the edit of this photo.

My aim was to reduce or simplify the image down to one subject : the graphic nature / shape of the lagoon edge. Remove the horizon line and the lagoon edge starts to float. It becomes the sole reason for looking at the photo.

And yet I know that most viewers will ‘construct’ or ‘invent’ a horizon if one isn’t present.

I’ve had to think about why I love making the horizon disappear in some of my photographs. I think there are several answers to this:

Pictures become more ‘mystical’, or ‘dreamy’ when things aren’t so obvious.

The mind has to work harder at figuring out what’s going on.

It reduces down and simplifies the image so it’s easy to ‘digest’.

The mind tends to fill in the gaps where there is missing crucial information. The viewer is forced into their own ‘dream state’ by imagining what isn’t there.

Which image really has no horizon?

As I promised you at the beginning of this post, here is the photograph that has no horizon. It was shot on a sloping field where the background behind the tree is actually the field rising up above the top of the frame. So I know from being there that the sky was never in the photograph.

Yet isn’t it interesting that we can’t help but imagine there’s a horizon in there!

I love playing with images where things are left open to interpretation. In my view, why should everything in an image be crystal clear? Why indeed do we need high-resolution all the time? And why do many of us strive to make everything so obvious to the viewer?

Well, my take on this is that for most of us, there’s an insecurity in worrying that the viewer may not see what we saw, feel what we felt. So we either tend to over-emphasise it (and almost everything else) in the edit to try to spell it out. And this can at best make the image too conventional, or at worst ruin it completely.

Final thoughts

I think it’s completely fine to leave things unanswered, to allow things to be inconclusive for the viewer. If it helps create an imaginary world of sorts for your viewer to disappear into, then it’s a feature rather than a problem.

This is why I love imperceptible horizons, because I know that often it’s best to leave as much of the interpretation to the viewer. It promotes engagement.