Momentum has a huge part to play in our development as photographers. Pausing when you are in the middle of a creative flow can derail you and set you back.

I was made acutely aware of this yesterday when I attempted to ‘resume’ editing some work I had begun editing two years ago.

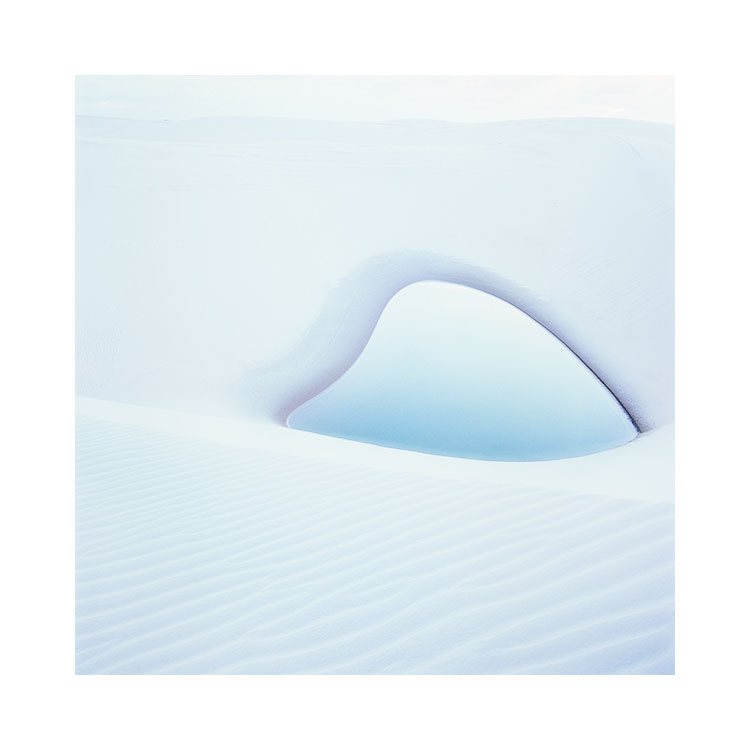

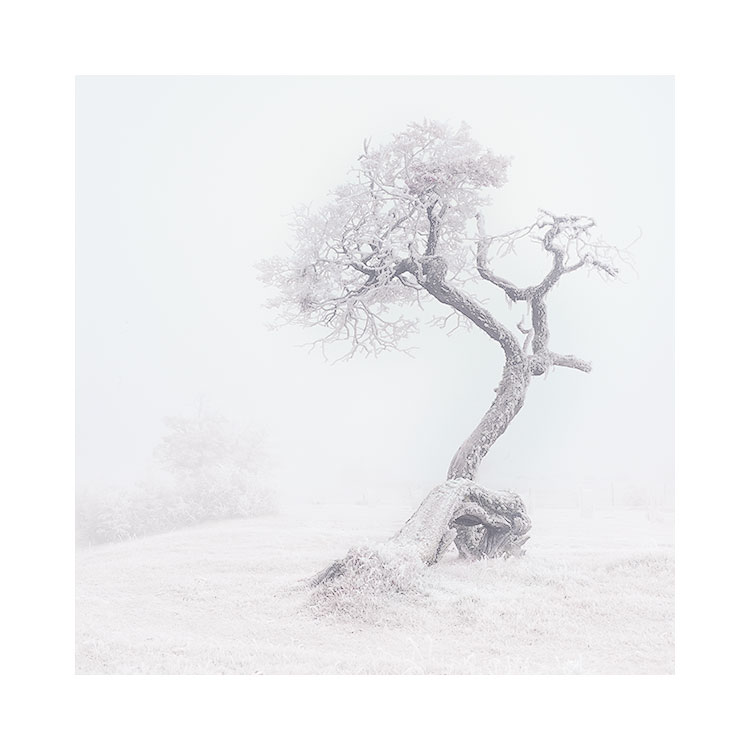

Let me explain. Two years ago edited I the set of images you see below. They were shot in Lençois Maranhenses national park in Brazil around May 2019. I felt the edits below were, and still are pretty good. Over the past two years I have always considered I got the edits about right for this collection. So I wondered this past week whether there were more unedited images in my films that I could add to this collection, if I resumed work on them.

I didn’t find much. Just one image (see above). And even then, it wasn’t so obvious. This process made me aware of several things:

1) When we are editing, we are often in a particular ‘creative flow’. Edit the images a week or two later and they will be different yet again, because the results have as much to do with how we are feeling and what we are ‘into’ during the the moment of creation.

In other words: editing is a performance.

It is one of the main reasons why I like to set a block of time aside to edit work in the same ‘session’. My head is going to be in the same place as I edit a collection of work, and I often find myself reliving the experience of the shoot.

So again: editing is a performance. Each performer / actor or musician knows that each time they play or act the same songs / scenes, they do them differently. And depending on their biorhythms, things vary.

2) I’d lost momentum. The ‘roll’ I was on when I created the nine or so images above had passed. Trying to get back ‘into that frame of mind’ was going to be hard. Almost impossible.

It took me a few false starts over a whole day before I was able to edit the top image to be anything close to an empathetic version of the original set. That is because it took me time to ‘adjust to the sensibilities of the original idea’, rather than it bend to suit me.

I have often thought of editing as a performance. Indeed, everything I do as a photographer has a ‘time’, is dependent on how I am that day. And trying to reproduce something later on to order seldom works.

Rather than think of this as a problem, I personally find it quite liberating. Because of the instability of how things might turn out, you have to learn to let go. You have to accept that some days are better than others, and this is quite a freeing idea. It removes the need for ‘perfection’. And allows room for give and take. For accepting things are they way they are, and is a strong reminder that creativity has an ebb just as much as it has a flow to it.