Photography isn’t about capturing what’s in front of us. It’s more about capturing what is within us. Often when I see workshop participants want to stop somewhere to make a photograph, it isn’t what’s in front of them that they are drawn to. Instead, they are drawn to an idealised view of what’s there.

I was laughing to myself when I saw this. It was simply too good to be true. Too symmetrical, too balanced, too orderly. Too close to an idealised view.

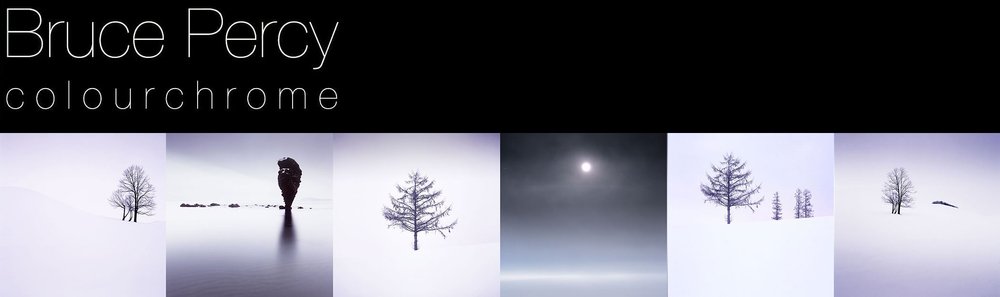

Image © 2019.

When we see a composition in our mind’s eye, what we do is take each element of the scene that is important to us, and discard the rest. Although the scene may be far from perfect, we focus on the parts that give us what we see in our mind, and discard the rest. This is often why many of us find our photographs never match what ‘we saw’ at the point of capture.

In other words: we have a tendency to idealise the view.

If we can find such an idealised view that requires little or no post-edit work, this is perhaps the goal we all seek. But it’s often not like that, and often most compositions out there are compromised in some way.

I think this is why I love Hokkaido so much. Although the landscape is heavily shaped by man, with a bit of work it is possible to find those rare moments when everything clicks into place and all the components before my camera lens fit into perfect symmetry. It satisfies my urge to make sense of the nonsensical, to make order of the disorderly, and to make pleasing compositions of random elements that come together for a brief moment in what seems like an intended way.