Although I love to edit my work and will often depart radically from what was there by using dodging and burning techniques, the final images you see here are pretty much verbatim. The only difference between the photograph of me on location, and my final images is that the sky clouded over once I got into the location, so there was more of a marriage between land and sky.

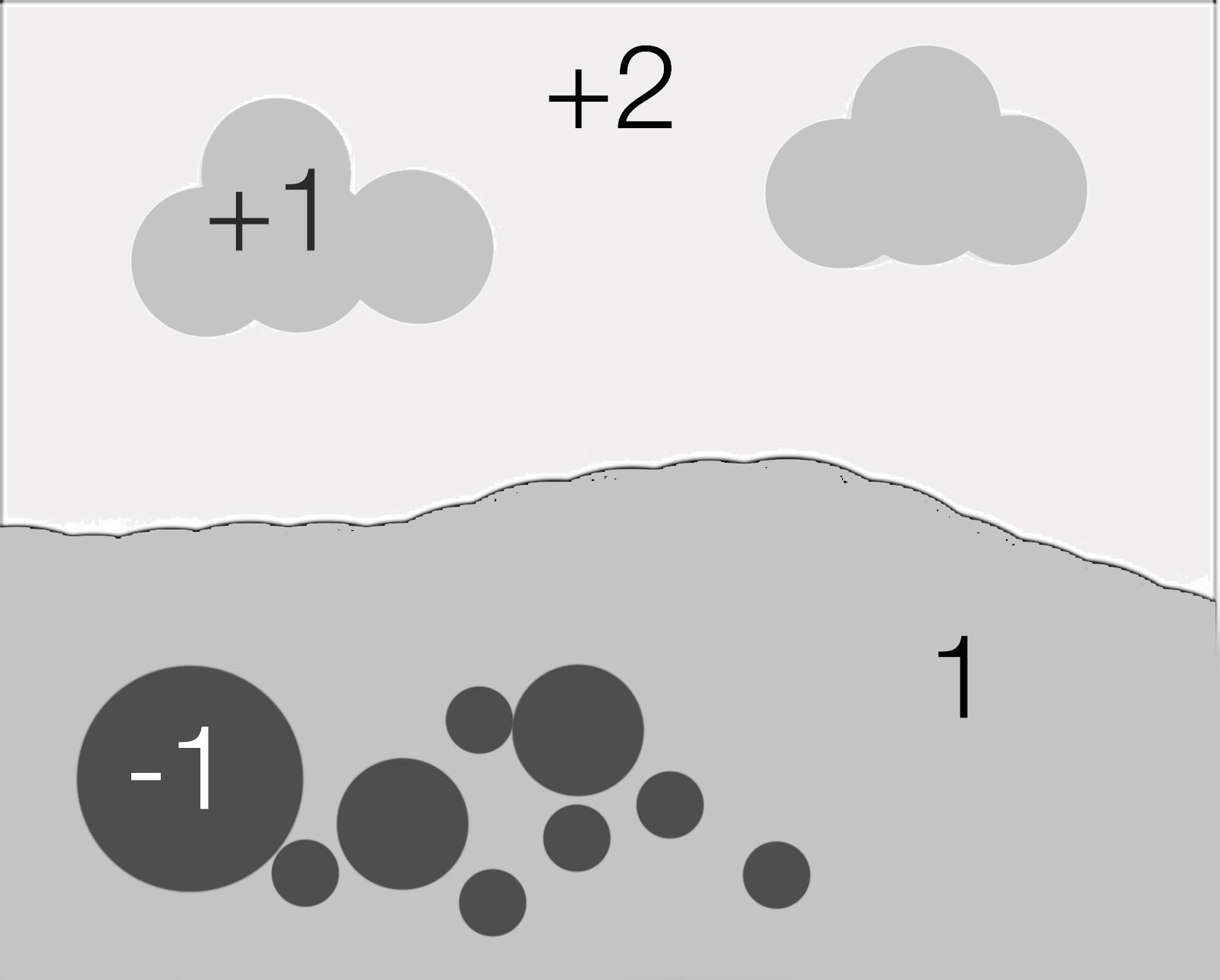

My only on-site decisions were more about placement - of where I should be standing to get different vantage points of the trees, and to be observant to any patterns that the trees made (see central image of the three trees at perfect placement to one another). Further, it was also paramount that I remove the background hedge from the shot at all costs, so I spent a bit of time looking for vantage points where the hedge would disappear from view.

I'd like to finish today's post by stating that often as a photographer i'm tempted to go closer towards the subjects I wish to photograph. Whether it's the edge of a lake or the edge of a cliff. This can sometimes be a real failing because of two points:

1) If you like your subject from where you are standing, then chances are it's not going to look the same once you get closer. So shoot it from where you've noticed it, before moving in. Practice using different focal lengths such as telephoto view to accomplish this.

2) As you approach a location you like, the elements start to move around and sometimes things get lost or hidden from view. See point 1.

Your journey can sometimes become an exercise in 'chasing rainbows'. You think that by getting in close, the composition will get stronger, but as you do approach, the scene falls apart and the subjects do not hold together in the way you first saw them. Often times, it's because the best vantage point was from where you started.

I'm glad to report that although I was worried that the big hike into this location, on snowshoes might have resulted in the trees becoming obstructed by hills, or by my being too low to photograph the trees straight on, the location worked beautifully.

I knew it at the time things were going well. As I slowly made my way forward, the trees and the compositions I had in my mind's eye remained in place. But I did keep an eye on how the compositions were changing as I approached.

I'm a great believer that when something is working well, whether it be in my photography or in my life, it tends to flow and come together easily. That's exactly how these images happened. It was as if they fell into my lap.