"We need space in our creative endeavours,

just as much as we need space in our photographs"

Often, I feel too much emphasis is placed upon the creation of work. But I think as artists, our non-creative time is just as important. We need to understand and most importantly, respect that periods of inactivity are just as healthy as periods of activity are. They give us a much needed pause in our creative lives to reflect and grow.

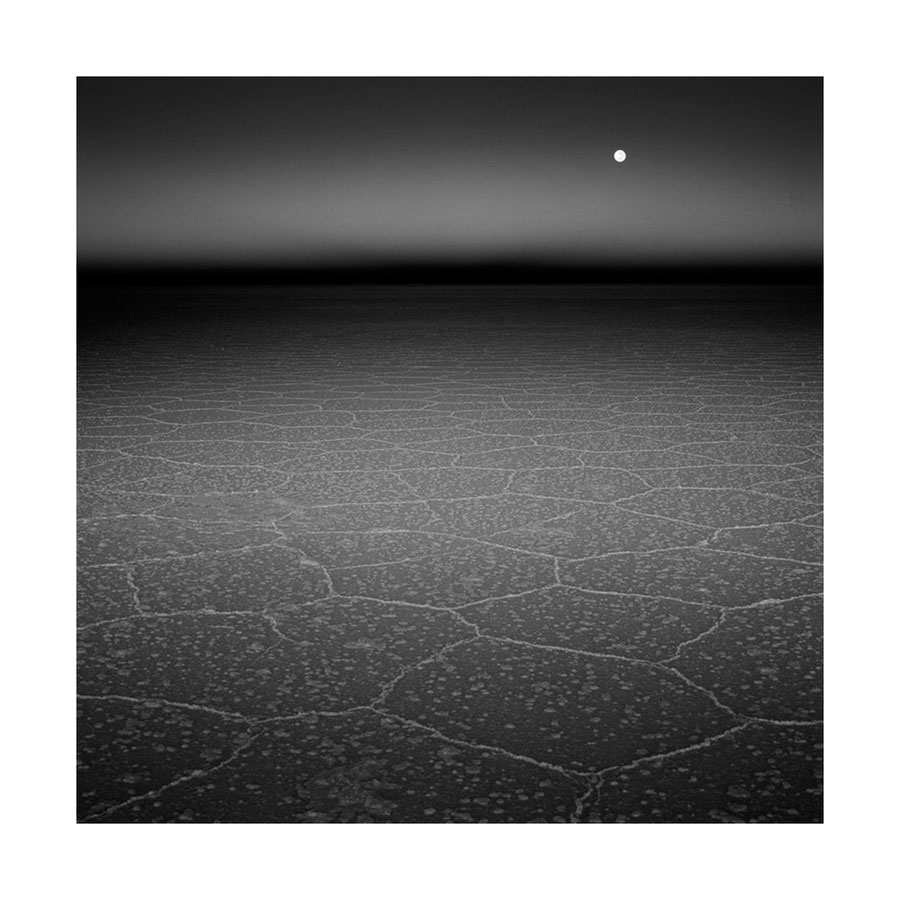

Moonfall, Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia. Image © Bruce Percy

Creative drought is often viewed upon negatively. There is a fear that since we cannot find any inspiration to create, or cannot create at will, that perhaps the creative well is dry for good. Our thoughts go along the lines os 'I shall never be able to create anything ever again!'

I think we should look more positively at these periods of inactivity and recognise that as with any creative endeavour, there is always going to be an ebb and flow to what we do. A yin and yang. To create, we must have periods where we do not.

I see these moments of inactivity as a rest, a pause in the music of our creativity. But there is more than just this, I've often found these periods to be the precursor to some new growth in my artistry. What I had thought may be the dwindling of my creative force, turned out to be the beginning of a new direction, or the reinforcement of a style in my work. The shedding of old skin.

If you are currently experiencing some creative drought - a bare patch in your creativity, I would suggest you accept it and let it ride itself out. Take your foot of the gas and wait.

Just as when we have a pressing issue that we do not have the answer to, I've often found that given some time away from it, the answer will come. As my dad has often said to me when I was trying too hard to get something to work: "best give it a rest for a while and when you do come back to it, you'll see it in a new light".