Back in February, I made my first ever trip out to Japan. It was a very enjoyable trip, mostly because the people there are terrific. Politeness is something that seems to be at the core of the Japanese, and I will definitely be going back next year.

The past few weeks have been deeply satisfying for me on a creative level.

I had originally gone out to Japan for a special one day event in Kyoto. I had high hopes that I might make some beautiful images of Maiko and Geiko (Kyoto's Geisha). All I can say about that day is that by the end of it, I felt extremely happy, feeling that I'd maybe made a few nice portraits.

I'm a film shooter, which means I have to live with the memories of those moments where I felt I captured something good. I think that's one of the reasons why I love shooting film. There is no pressure to review immediately what I've shot, and I go with the philosophy that what's done is done. It allows me to live more in the present moment. No stopping to review, just making images. Which is great.

Once I click the shutter, the image is either imprinted on my mind or it's not. I have to listen to my gut a lot and the more memorable images tend to stay with me in my thoughts and feelings for days after the event. I find it highly enjoyable to let my mind settle and absorb what it was I experienced. I often feel it takes a lot of time, maybe weeks or moths to really be clear on what I experienced, and in this way, it's great to just leave the films until I get home and have space in my mind and schedule to work on the images.

So this posting is really about the experience of watching new work come to fruition. In my studio I have a light table where I place my transparencies, and I also have a daylight viewing booth where I can review the contact sheets for the negatives I've shot. The Geisha portraits I made were shot on Kodak Portra 160 colour negative film, so I always request a contact sheet to be made, so I can easily look over the entire collection of images on a roll in one easy go.

During the selection and editing, I've felt I've been getting re-acquainted with Kyoto and my the day I spent there making images of Maiko and Geiko. It's been such a really beautiful thing to get absorbed in the sights and memories of the trip and also to find that the certain images that really made a big impression on me at the time of shooting, have reliably met my expectations. But there is also the beautiful surprise in seeing other images I had not thought would make the grade come to life, and to watch the final portfolio take shape.

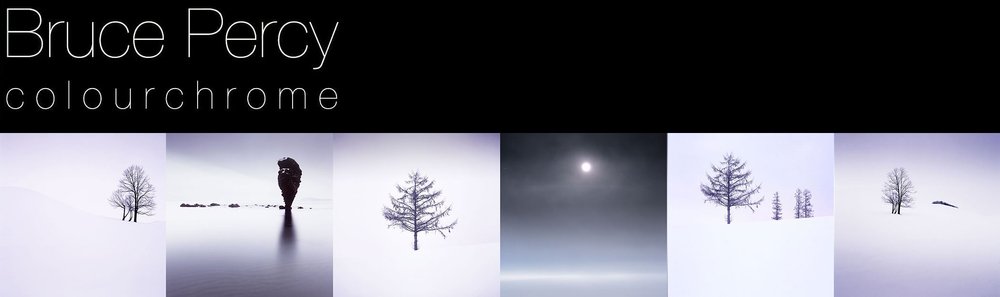

Each portfolio should have it's own vibe. Sometimes that vibe is based on the subject matter, but more so for me now, the collection of images has to have a cohesive feel to them - usually brought about by the colours and tones present in the work. I often feel my own images tend to speak to me and dictate how they are going to turn out, and it's up to me to see relationships in colour ranges or subject matter to find a common theme or story while I'm editing them.

The past few weeks of sitting in my home studio absorbed in contact sheets and watching the portfolio's story appear before my eye's has been really wonderful.

One mustn't rush the editing. When you have just made a collection of images it's all so tempting to get back to your home and busily start work on them, but there's really something wonderful to be had in cherishing the moment because it is a way of recalling the experiences and feelings you had whilst making them.

My new collection of images can be viewed in the new work section of this website.