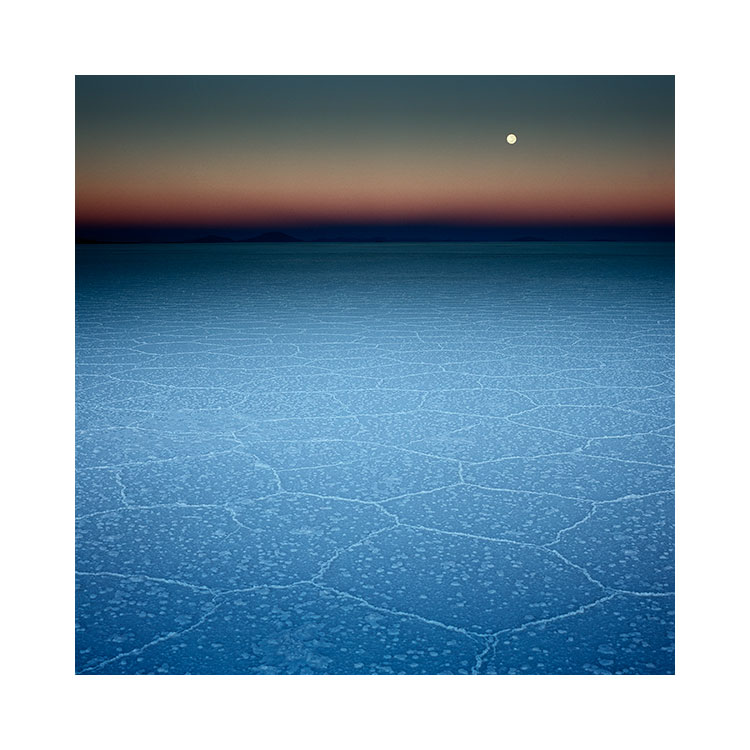

Conversely, being told exactly what the picture is, or what we should get out of it robs us of being able to attach our own emotions and thoughts.

I remember looking at some of Paul Wakefield's wonderful landscape images on his website. There were no titles, nothing to give away where the images had been made. I thought I recognised one of them as a place I frequently visit but there was something new about it, a different perspective that made me think again. So I emailed him to ask if it was where I thought it was, only to get the reply "don't you think an image is more compelling when you aren't sure where it is?".

I agree.

Not only are they more compelling, they are also free to be whatever you wish them to be.

When Paul finally published a book of his images several years later, there was a page at the back of the book that told me where the locations of each image were. By this time I had become so familiar with Paul's beautiful images that I had attached my own impressions to his images, so much so, that finding out that they weren't where I thought they were - meant that my attachment fell into question and I found myself having to revise my thoughts about them.

It was more beautiful when I hadn't known, when I was free to create my own ideas and impressions of where his images were from.

We attach so much to an image upon first viewing, and as we go back to our favourite images we keep reinforcing our own emotions into them. We make up dreams and ideas about images that we love, the same way we make up dreams and ideas about songs we love. This is why I have never enjoyed watching music videos because they often force me to discard my own personal interpretation of a song and instead force me to take up the view of the video.

Describing, or giving emotive titles to images gives less freedom to the viewer to take up their own view. But what about images of anonymous places? Do they hold similar appeal?

I think they do.

Rather than shooting the iconic well known place that everyone knows of, we are left to wonder - 'I don't really know for sure but there are aspects about the picture which make me think it could be Scotland, but then again, there are other aspects that make me think it could be Norway'...... Anonymous places have so much power to bewitch us.

Don't you think this makes the images more compelling?

Special thanks to Dorin Bofan (a fantastic photographer in his own right) for the kind use of the image of me in the landscape photographing a rather snowy, frozen tree, and to Florin Patras for putting together the trip where this photo was made.

More later, once I get my films back from the lab!