Great photos aren't about pixels. Neither are they about resolution. They aren't about technology and they aren't about plug-in's or software. Great photos aren't about the camera we used to make them.

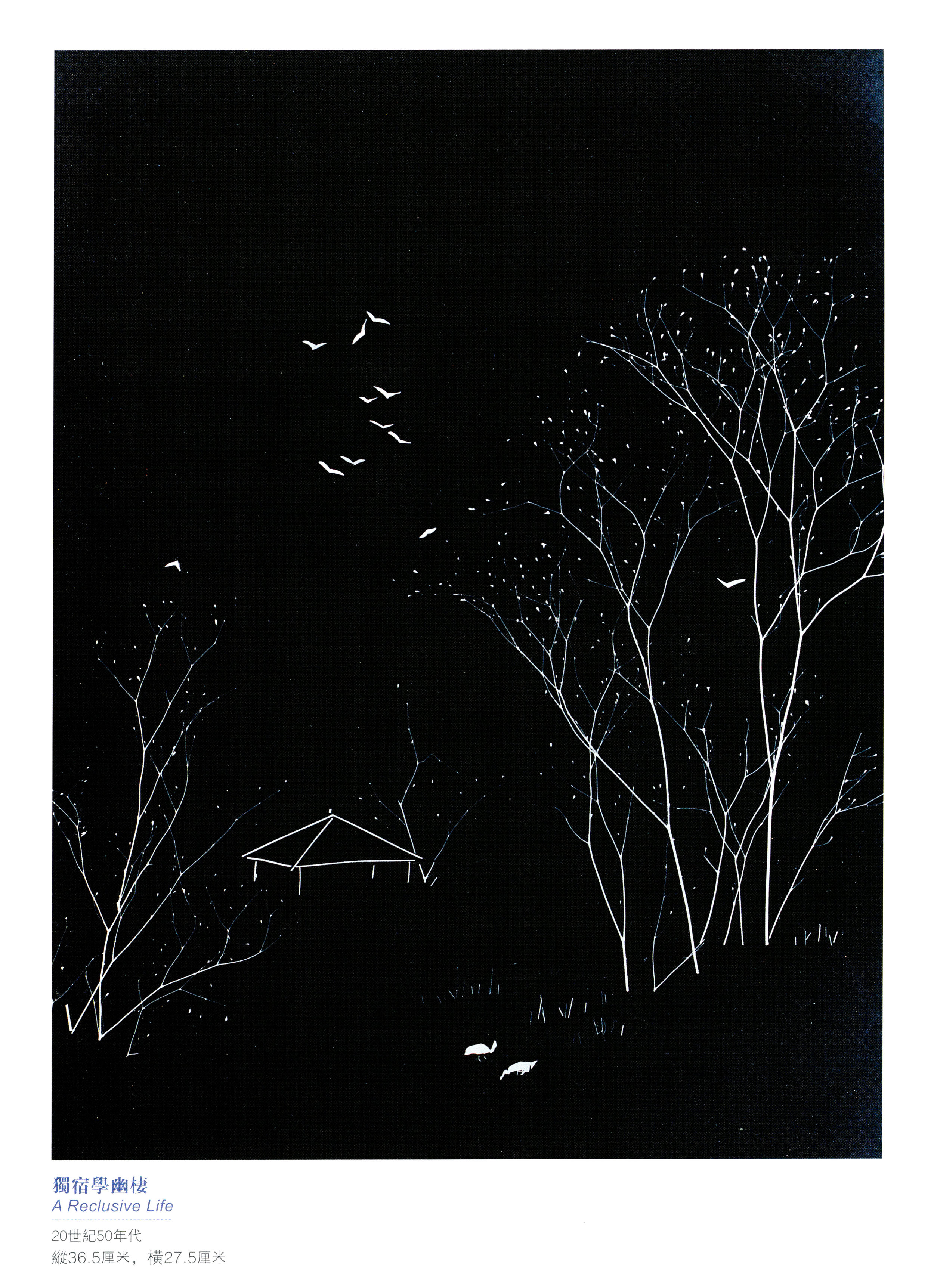

Great photos are about engagement. They are about having a great idea, a strong composition to start with.

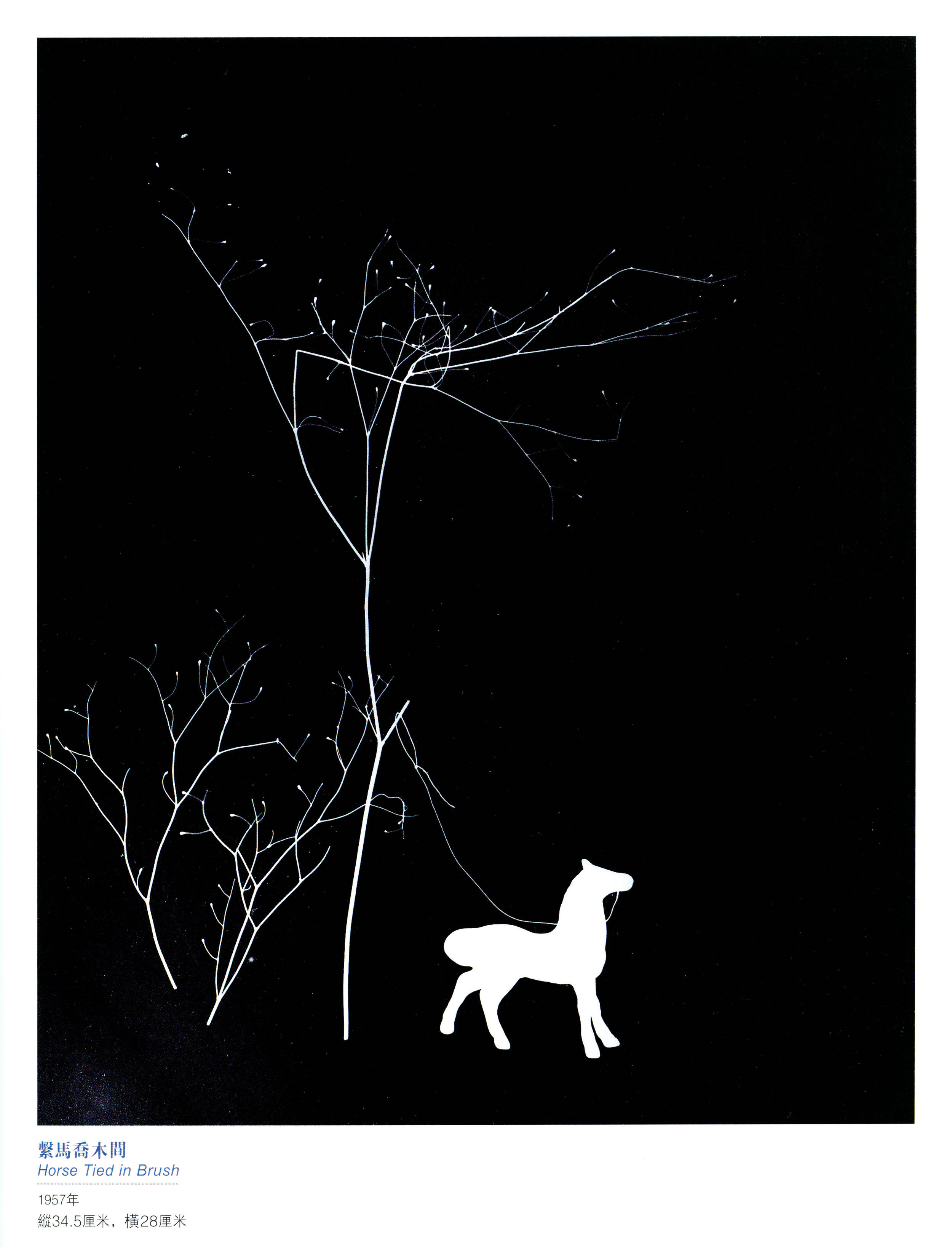

Much like a good story, good photographs don't need to be supported by gimmicks. Just as good songs don't require expensive production techniques to make them good, great songs can be played on simple instrument because the strength of the idea behind them carry them along.

Good images just need a good idea. They shouldn't need much more to make them work.

Yet we live in an age where we can become lost in the technology. Where we are convinced we need another software-app, HDR, Focus-stacking or to blend images to produce good work. This is not true. We just need our images to be strong ideas to begin with. An ill-conceived image will always be an ill-conceived image, no matter how much gloss we apply to it.

Jon Hopkins shows us that some very simple chords on a piano can bewitch us. Strip it back and it still works. It's a reminder that great ideas have a knack of carrying themselves.

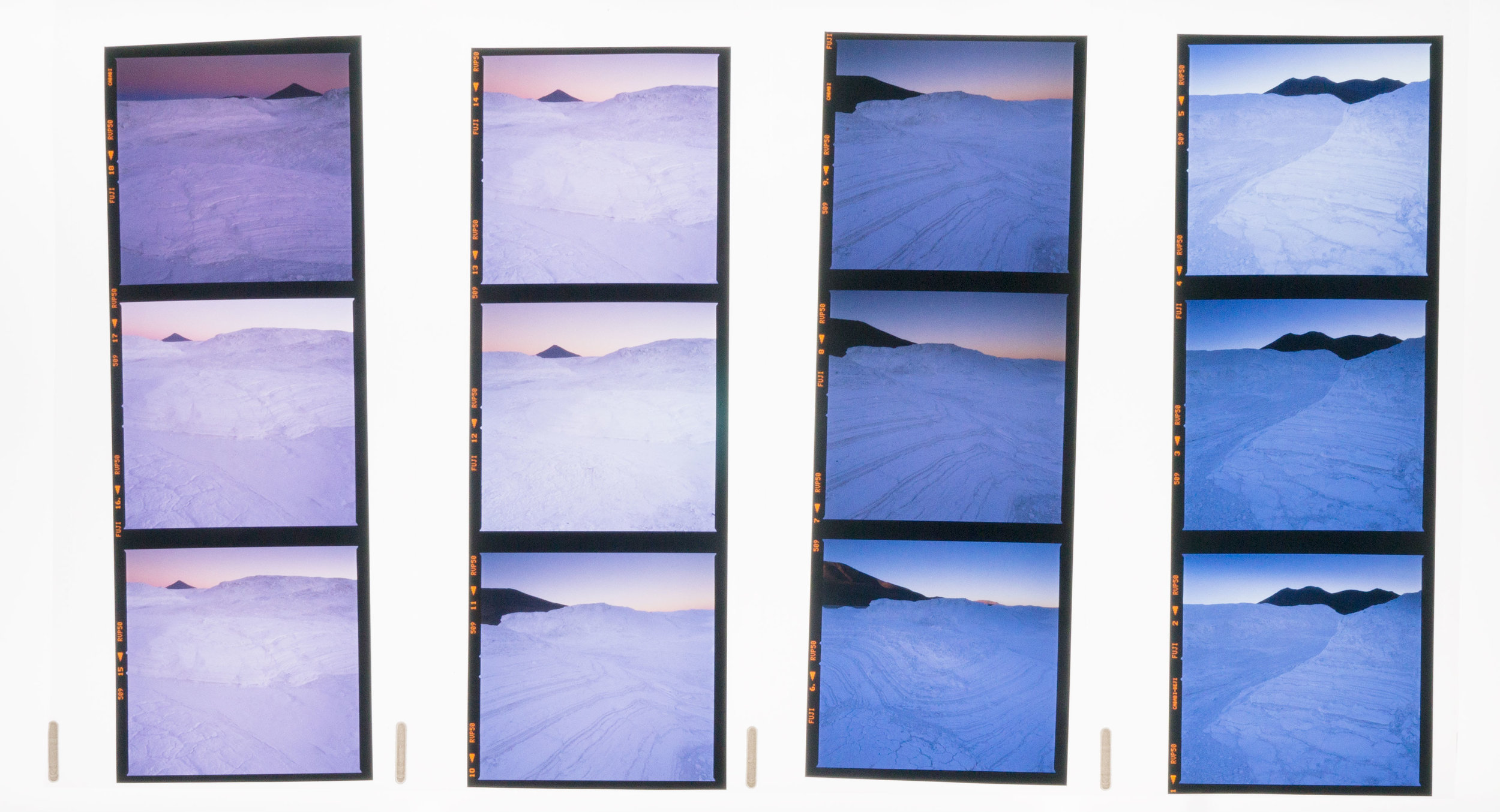

When I'm out making images and selecting which ones to use later on, I always respond to how I feel about them. If they are strong, I usually know because strong work tends to let you know what it wants. Like strong song ideas that tend to write themselves, good images tend to come from nowhere and dictate to you what needs to be done.

Weak work on the other hand doesn't. Weak ideas often lack conviction and send confused muddled messages about what they are and where they want to go.

If you want to improve your photography, then I would suggest you dump your technology. Put to one side the HDR, focus-stacking, blending, software-apps for a moment, and instead, go out and listen to your intuition as it's the best photography tool you possess.