As someone who makes photographs that are often cited as having some form of simplification about them, I've often found it hard to explain how I come about my compositions.

In this TED talk, I think that Roman goes a long way to helping me explain how I simplify my compositions. By discussing the design of Flags and why some flags are better designed than others, Roman explains what 'good design' is.

Once we understand what 'good design' is, it doesn't take much to realise that it can be applied to almost everything we see around us, which Includes photographs.

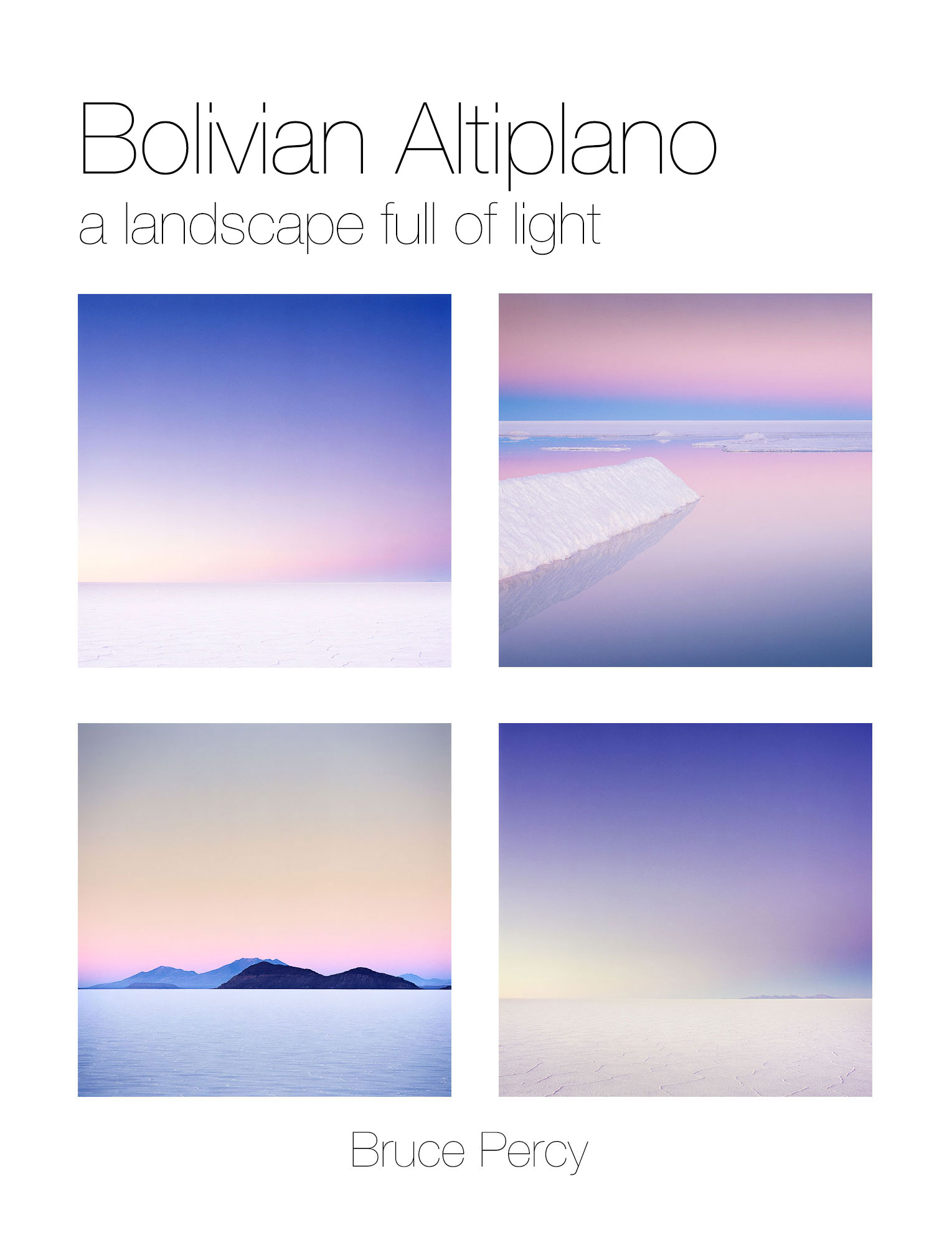

For example: a good flag will look effective when viewed as a tiny thumbnail image. Most flags are viewed from far away, so if the design doesn't work at such a small size, it's probably too complicated. I find parallels in this idea with my own imagery. Often the images I choose to edit or work on look good when viewed as thumbnails. I can often see the underlying structure or simplistic forms that make up the core of the image when viewed really small. Complex imagery doesn't tend to work when it's reduced to a very small thumbnail.

On a related note, I find that making well designed photos is not enough if you want to be a good photographer. How we choose to present out work - the design presentation - can influence how others perceive the work and ourselves as photographers. If the presentation is smart, clean and simple, then the work has a chance to live up to its full potential, but if the work is presented with little thought or care, it can be received less well.

Design goes right through everything we do as photographers - from our business cards, to website layout, to how we present our work in book form.

So often I've seen beautiful images badly conveyed because there was little or no thought in how to present the work. Good design is important.

It seems that flag design is more important than I realised. Watch the film - it's a fascinating insight into how design is everywhere and how it really matters.