I've been working on a new e-Book for some time now - 'Tonal Relationships'.

Each time I begin work on a new project, it can really take a while to move off the landing pad. I found this to be particularly true when I wrote my Fast-Track to Photoshop e-Book, which actually took me about two years. Most of it was a sense of procrastination because each time I approached it, I felt I was tackling it from the wrong perspective.

A work in progress. It's better to release something when it's right. It may be some time yet :-)

I'm a great believer in sleeping on things if I don't know the answer. Backing off from something and giving my mind the time to collate and make sense of something works really well for me. I've found that adopting this approach to my photography, as well as writing e-books and also in life experiences, has been invaluable.

I found that just by leaving my 'Fast Track to Photoshop' e-book idea on the shelf for a long long while, I seemed to get clarity on how it should be formed, and when I did get round to writing it, it all came out very easily and I felt I wrote one of my most clear and concise efforts to date.

Well, I'm not there yet with my Tonal Relationships e-book, as I've been having difficulty trying to figure out how to proceed, but I've noticed that over the past few weeks I've started to formulate a structure for how the e-book should be laid out and things are getting clearer in my head.

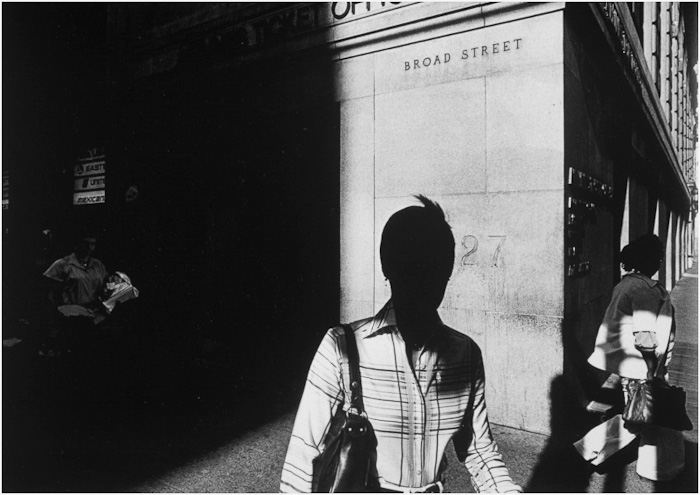

One aspect that has become clear to me over the past few years, is that tonal relationships do not just have to work within each single image, but in order to help with defining your own style, I think the tones should remain consistent through any body of work you produce. For instance, I've noticed that when I convert my colour work to monochrome, I'm able to see how consistent my work is - strip away the colours, and the images still appear to be very balanced.

It was only when I converted some of my existing colour work to mono, that I discovered how consistent I was with my tonal ranges in my work.

Anyway, I digress a little. Here right now, is a rough idea of how I feel the e-Book may be laid out. I'm always open to things changing, and trying to not be too fixed on things, because creativity needs the space to go where it wants to go.

Main ideas of book:

- Relationships throughout the frame - by strengthening one area of the frame, other tones are affected

- If you make two areas of the frame the same tone - they become related.

- If you make two areas of the frame different, they become unrelated.

- The odd tone out is the dominant one. If you keep one area of the picture different from the rest, it becomes the dominant tone. White stone on black background, or black stone on white background

Fieldwork Awareness Section

- learn to think about tones while out making pictures: abstraction versus association

- being aware of colour constancy / chromatic adaption while you work under different lighting conditions, and applying this to your choice of subject

- Avoiding overly complex tonal compositions

Darkroom Workbook Section

- Transposing Tones - take one tone in the image, and shift it (harris hills in harris photos)

- Look for images in your collection that have very few tones. Edit them so all the tones become more similar

- Simple compositions aren’t necessarily of one or two objects. Sometimes they are simple because they contain one or two dominant tones. Busy images can have too much tonal information in them.

- Image selection: choose those with simple tonal relationships, because it will make the task of editing them easier.

- image selection: when toning one image, refer to others in the collection for guidance. Often one image will dictate how the others should be edited, so they 'sit together' better.

- Is your eye being pulled all over the place by too many tonal distractions? Apply localised contrasts, or reduce contrast in other areas to bring emphasis to other areas.