Been a bit quiet this past few weeks. I’m in the middle of processing films from my recent tours to Brazil and Bolivia.

Below is a photograph taken on my phone of my light table with Velvia transparencies just dried, and in the process of being cut, and put into a sleeve to protect from dust.

9 images from one roll of film, on my light table.

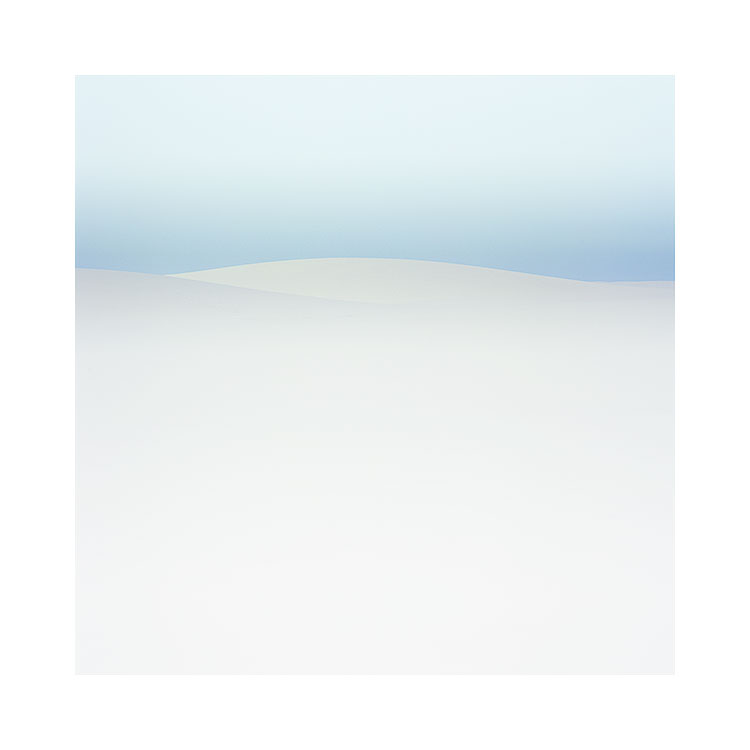

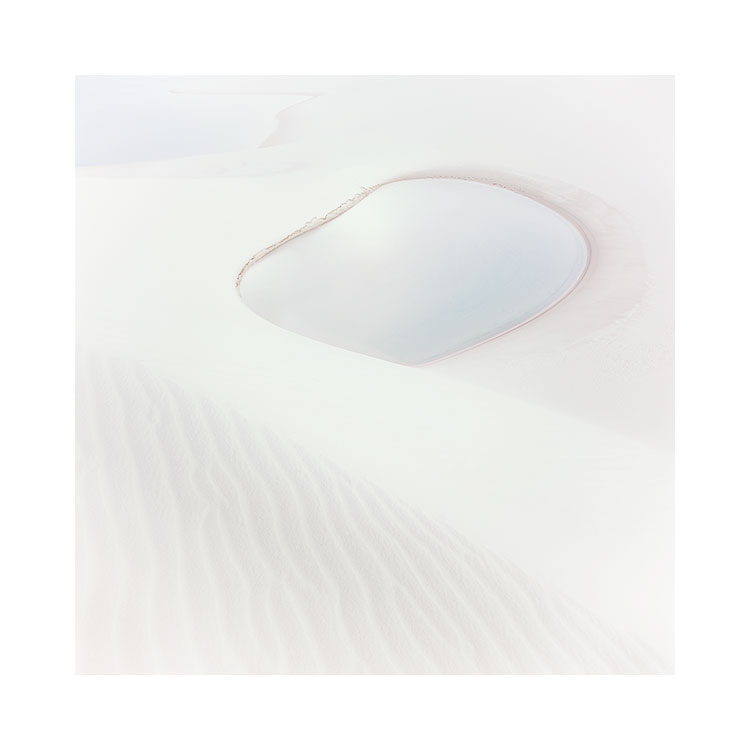

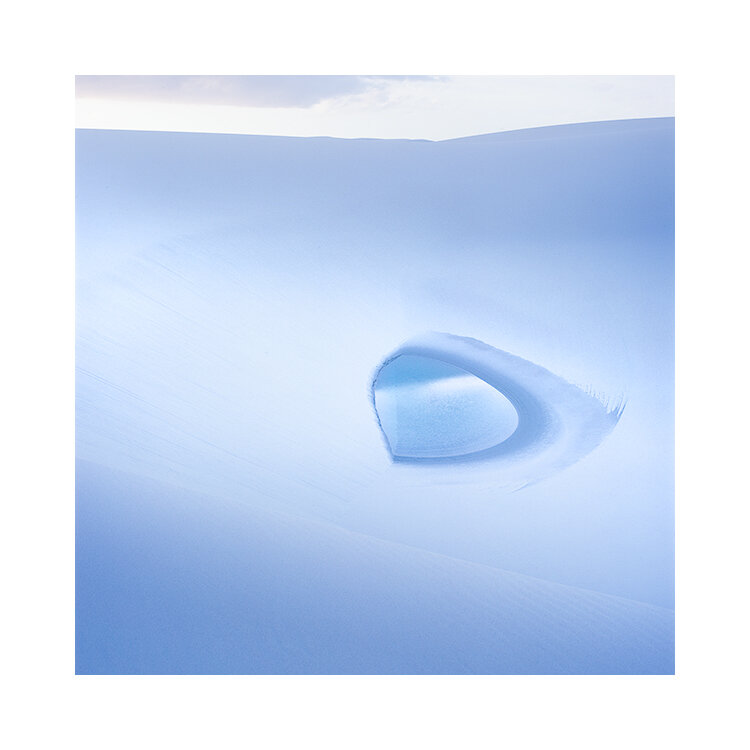

One of the things I loved about this year’s tour to Bolivia was that we had a lot of overcast light during the day time. My fantastic guide Silveria wanted to show me two of the islands on the Salar because she loved the shapes of them: pyramid and some kind of flying saucer shape. I have worked with Silveria before and she seems to understand and know what I’m looking for : graphic shapes and simplified composition.

Anyway, if there is a point to this post today, it is that even though I have been coming to Bolivia now for over a decade, there is often a chance to see something new. Partly it’s a case of being taken to new views, other times it’s that the light is different. But on this occasion, I know within my heart that what I am attracted to make images of these days, is quite different from what I was looking for back in 2009 when I first ventured here.

Bolivia has been a learning landscape for me. It is often easy to see our progress when we look back, and when I review and study my first efforts, and how the compositions seemed to become more simple as time went on, I gained so much in noticing that there were elements and traces of where my style was going to progress to, in the initial images from all those years ago.

I’m almost finished processing the films from the past year. I hope to start working on editing and publishing images from Bolivia and Brazil over the coming weeks. We will see.