Puna de Atacama, Argentina. Wednesday 28th of April 2022.

My guide Pancho took this photo of me in the Colorados region of the Puna de Atacama. Each time I have been here, I never quite know when to start shooting. While the light is on the actual mountains, their contours are more clearly defined. But I feel the images lack any particular atmosphere when they are made during daytime lighting, and so I often wait until they go into shadow.

My guide is always saying to me ‘the light has gone’, and I have seen many photographers in my travels pack up at this moment and go away. But this is often when the light may start to get better.

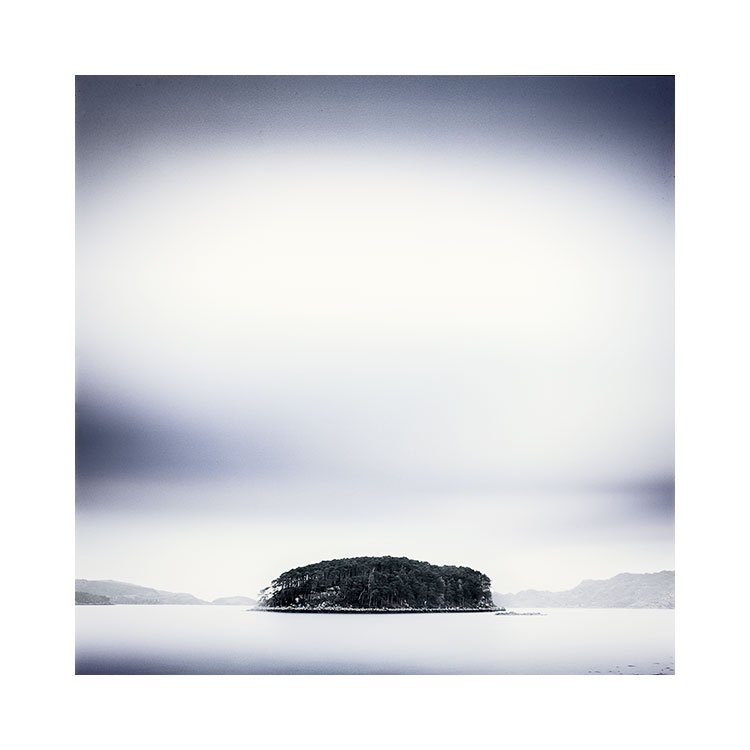

In this case, around 10 minutes after sunset, not only were the mountains in shadow, but the sky had darkened down also, and everything now appeared to be glowing. It is as if the light is coming from all around me during these times, but what has really happened is that my eye has adjusted to the shadowed landscape and the more muted sky.

After the sun has gone, everything starts to glow

Think if you will, of an aperture being opened up. My brain is now interpreting this shadow light as ‘daylight’, and so even though the EV value is much lower, it now appears more balanced and easier to look at.

The main reason for shooting once the sun has gone, is that the shadows are greatly reduced. The tonalities are much softer. One danger about this is that by comparison to the ‘daylight’ shot, you may be tempted to believe that there is no definition in the contours of the landscape. Not so! The contours are still present, but they are softer. More easy to work with when editing / printing.

This is one of the more alluring times to make photographs. But I would suggest that you make photographs from just before the sun starts to go down, until well after into the twilight time. Review the images later on with the view to studying the tonalities, contrasts and also to note that the entire duration from pre-sundown right through to twilight can produce good images. Just don’t stop once the landscape has gone into shadow, because you may be missing out on the beautiful light you see in the above photograph.

Ambient light is still falling on your subject after sundown

One last tip from me, is to shoot 180º to the sun. I always shoot with the sun behind me, or to the side. Rarely towards it (unless I am deliberately looking for silhouettes). The contrasts are extreme. Whereas shooting who the sun either behind or to the side of me, allows for light to fall onto the subject. It may appear as though this would not matter once the sun has gone down, but the truth is that there is still a lot of ambient light falling on your subject. There is always a flow of light particles still hitting your subject.

Even well after sundown, when everything is black, if the subject is facing where the sun was, your camera will still be able to record ambient light that is still falling onto your subject. Your camera will still see it, even if you aren’t able to.