It’s my view that trusting one’s initial emotional response to a scene can have two possible outcomes;

1) a strong idea

or

2) a derivative one

And I believe that at the point of capture, we often don’t know which one it is.

To put it another way, while making photos, it is impossible to be an editor. It is impossible be able to successfully judge what we are doing, while we are doing it. The judgement and review of what we are capturing should therefore come much later.

So my view is: just because I’ve found a composition that I like, I cannot trust my judgement that it is the best one available. Although I may believe it to be the strongest composition I’ve found, I have often found that there is usually something much stronger, if I keep looking.

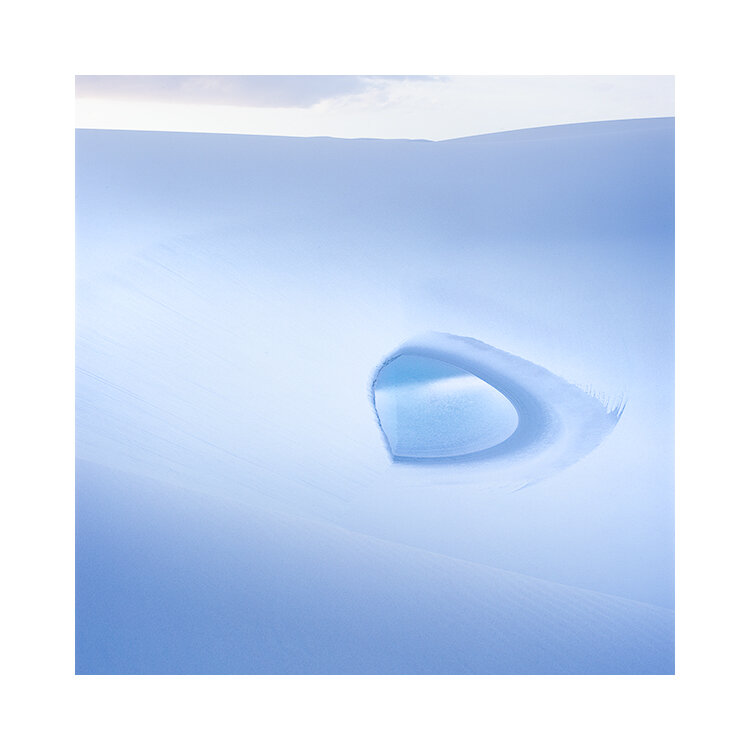

So these days, I tend to make variations of the same shot. Each with some kind of alteration. Whether it’s moving forward slightly, changing the proportions of sky to ground, using a different focal length, or just focussing on a different region of the same scene, as can be seen in the examples in this post today.

I therefore believe that we have one task at hand while we are shooting. We are content gatherers. We are there to collect material to work with later on.

This may sound rather heartless to you, and may suggest that we’re just there to collect raw stuff to make sense out of later on. I do not mean this at all. I simply mean we need to consider all options while we are on location because often the best shot isn’t the obvious one.

Each time I fire my shutter, I put 100% commitment behind it. I am thinking ‘this is perhaps the best frame yet’. But I am also thinking ‘there may be something better if I reconsider the scene a bit more’. I am therefore making insurance shots. I understand that I am in no position to judge what I’ve got, so I better keep on looking in case there is something better.

Judgement of what I’ve captured should come much later, when I am ready to edit the work.

And so if we go back to my initial statement:

It’s my view that trusting one’s initial emotional response to a scene can have two possible outcomes;

1) a strong idea

or

2) a derivative one

And I believe that at the point of capture, we often don’t know which one it is.

And so, it’s hard. Hard to judge whether what we are reacting to is a strong idea, or a derivative one. Once we get past this worry and decide that this is a question for much later, we open up ourselves to what is in front of us, and we become more immersed in the act of creating images.