I'm holding another exhibition later next year (Summer 2019), t

The last few weeks I've been working on the image selection for the forthcoming book, and we have now completed this, along with the text that is going along side the book. Currently I am awaiting Spanish translations as I feel that since this is a book about a region of South America, it should honour the landscape by also having a Spanish translation.

What I found last year about preparing my book, was that I really needed to print each image out to ensure they were optimal. When I did print them out, I noticed that some of them didn't have the 'sparkle' that they seemed to have on my monitor (even though my monitor is tightly calibrated). Some things needed to be pushed so that I was using the tonal range of the paper. It was a fascinating thing to do, as you can so often think the image is finished on the monitor, only to notice discrepancies in the tonal range once printed.

Once I had completed the printing of all the images that were to be contained within the book, I then replaced the original files with the optimal ones. So in essence, the images that were contained within my 'Colourchrome' book were the result of fine-tuning by print-review. Most important and I would urge you to do the same for any image you work on: print it out and evaluate it. Sit with it for a while and see how your impressions of it changes over days if not weeks. You'll be able to notice problems in the image that you weren't aware of on the monitor.

And so it comes to which images to prepare for an exhibition?

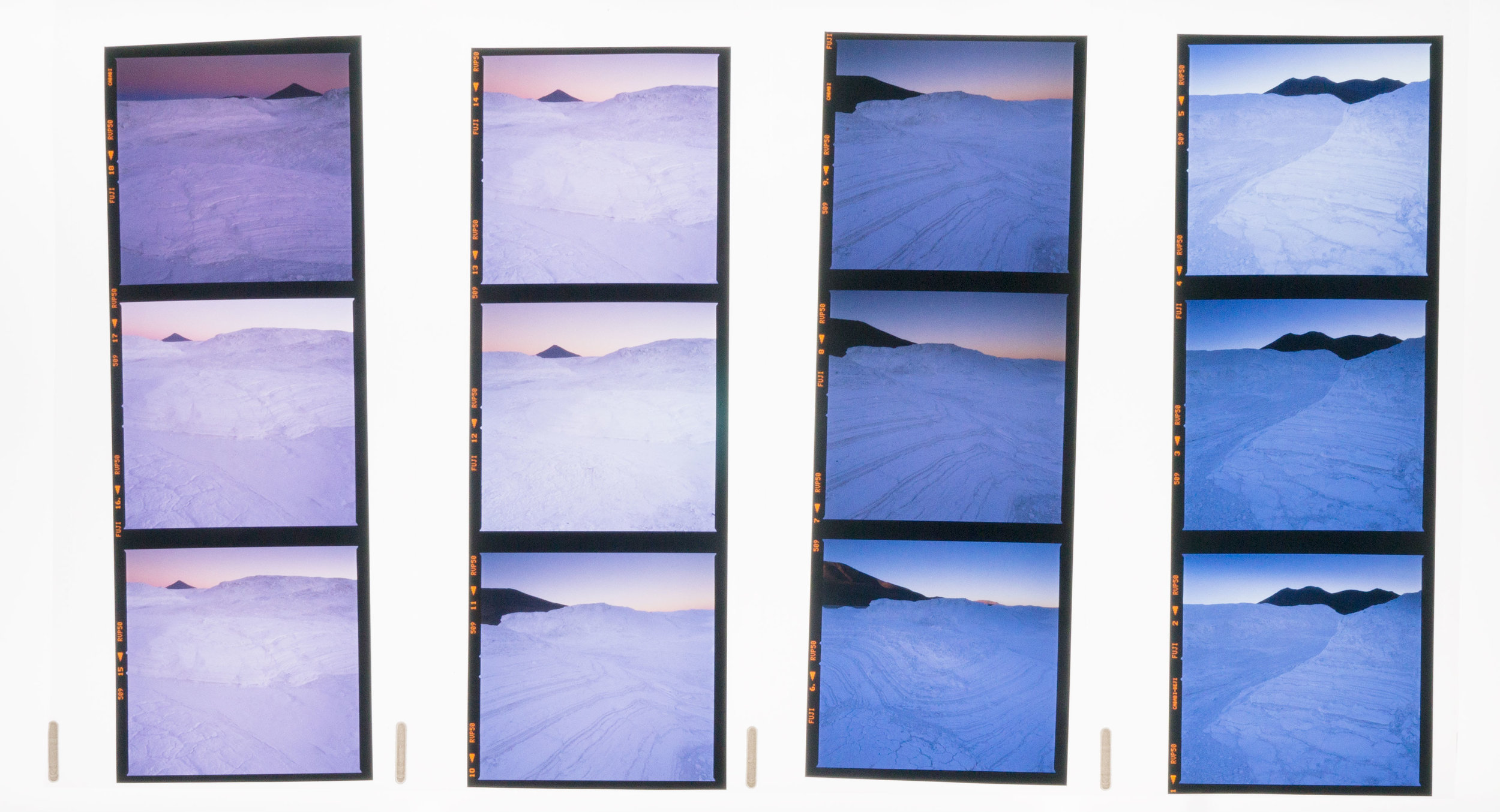

If you are considering doing an exhibition (I highly recommend it : everyone of all abilities should exhibit their work: it is the final stage in photography in my opinion), it's a good idea to go into the exhibition space and take measurements. My dear friend Alan Inglis suggested this to me when I was in the initial stages of looking for a location to exhibit. He came in with me and took measurements of the walls and also made some iPhone photos of the walls too (the images you see here).

Once we'd done that, I could set up mockups of the actual frames, all to scale of course, so I could experiment with a layout.

This is what you are seeing on this post today. I have chosen a selection of images and laid them out whilst trying to give them sufficient space, while at the same time maximising the number of images I can display (the more you show - the more value and interest to the viewer).

Last year's exhibition was terrific. I really enjoyed the experience: I got to meet so many people from past workshops and tours who came in to say hello. I also got to meet people that have had me on their radar for sometime, yet I was not aware of them. And the exchange in discussing your work is not to be underestimated.

Once I'd finished the exhibition, I was sitting around thinking 'now what?'. What do I do next? So I asked my favourite Photographer - Michael Kenna that, and he said:

"Hey Bruce,

You should have a show every year - include a few classics and show new work.

It will keep you on your toes. Sales may not increase - that remains to be seen.

But, it’s a good way to measure your own progress. Specific goals and deadlines always make us work a little harder."

Well, you heard the man. He knows a thing or two about exhibitions. So I chose to listen to what he has to say and decided I would do another one this year.

About the mockup's : that is exactly what they are. They have given me the opportunity to see what the final exhibition may look like, and I have been able to move and swap things around till I get the 'flow' right. What is most inspiring of all though, is that by visualising the final exhibition this way, it all just begins to take on a more 'real' aspect. You feel you are one step closer to your goal! I always try to use visual pictures to help me see where it is that I am wanting to go, whether it is mockups of exhibition spaces, mockups of books I want to produce, or even mockups of future workshops I hope to hold.