Sometimes I overlook images. I don't see them, don't recognise them for their beauty. It's a talent I have, one that I think most of us have to not truly see what is before us :-)

As part of reviewing work for my upcoming Altiplano book this year, I've been finding work that I can't quite understand why I passed it by. The images are very beautiful and yet I failed to embrace them at the time I was editing.

We all do it. Sometimes we don't see our work for what it truly is (this goes both ways - sometimes I think it's better than it actually is, other times I don't appreciate the beauty because I am so hung up on how I wanted the image to turn out, and don't accept it for what it offers.

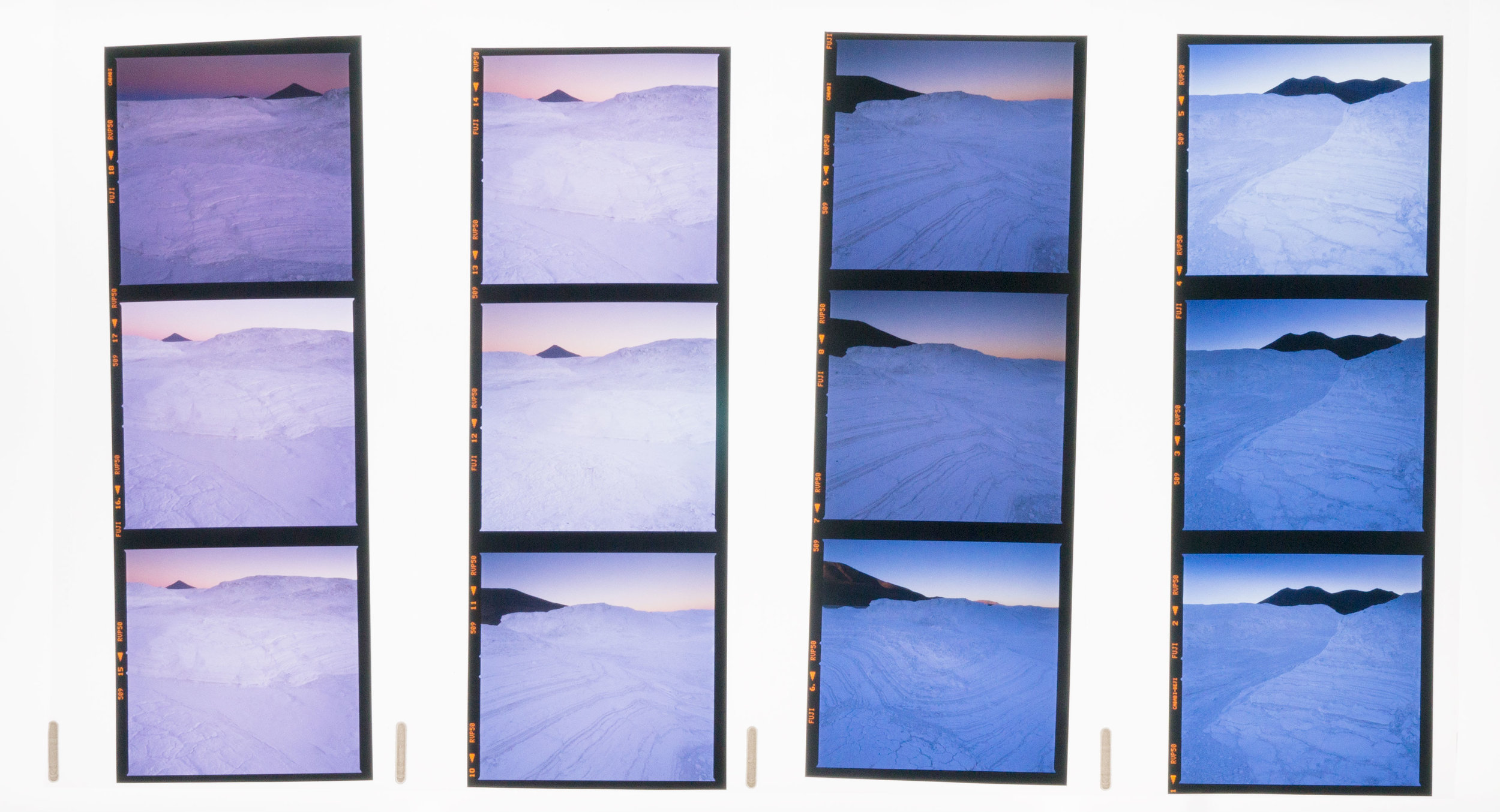

There's a remedy to this: every once in a while, I go back to my older images and review them ( in my case - I look at the unscanned Velvia transparencies). I then focus on the work I didn't use and try to see if there's something there that I missed first time round.

I can guarantee I will find something for sure. Either because I was too focussed on other things to notice it, or I was simply too close.

One of photography's much needed skills, is the ability to review oneself. To do that, you have to be open to what you've done, accept the failures as much as the successes, and to be as objective as you can be.