It's been a while since I wrote about this, and I've had a few people contact me about it. It seems that my original posting had lost some of the charts for reciprocity with Fuji Velvia, so I'm re-posting it here.

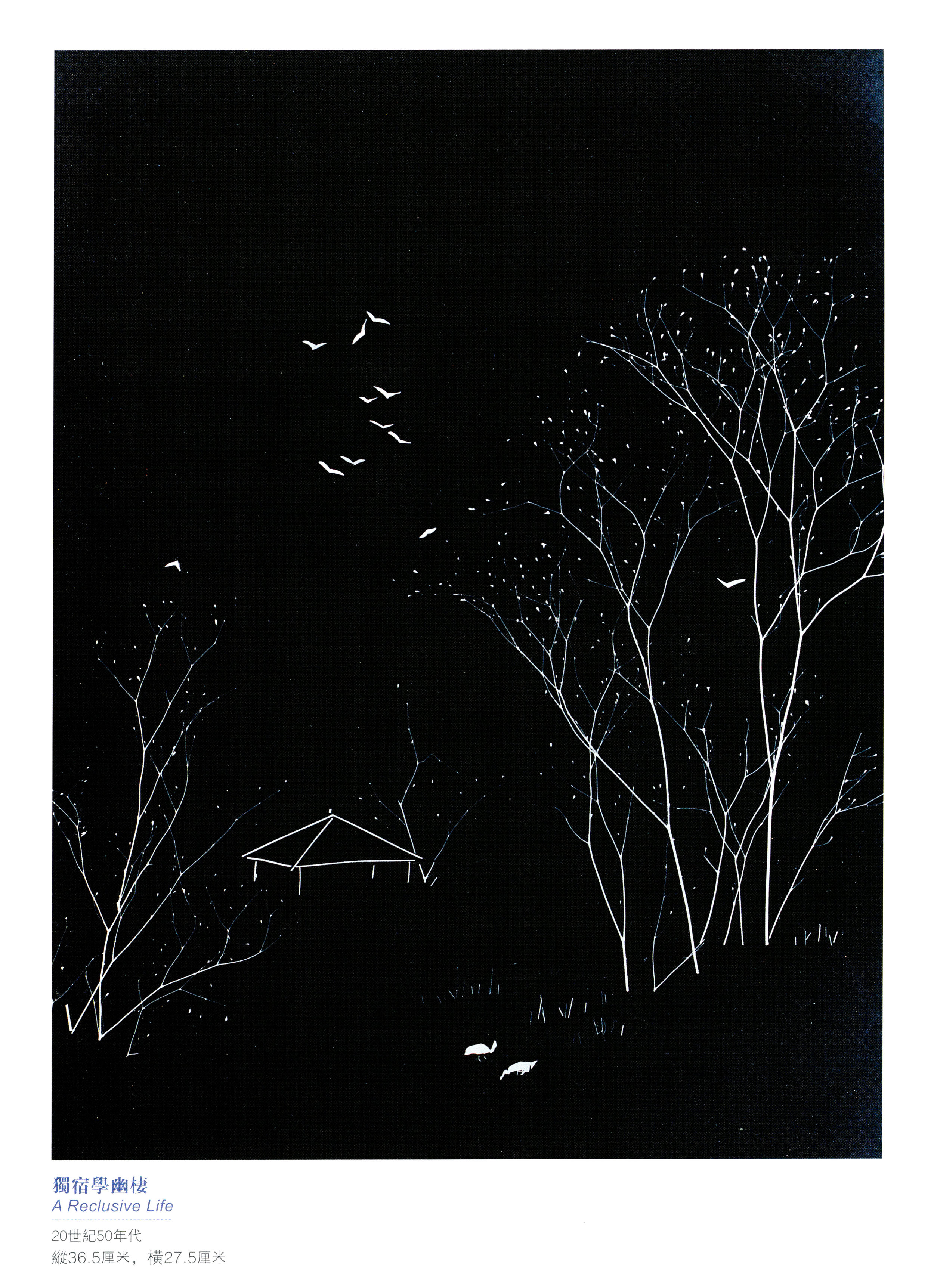

One of my most favourite things to do with landscapes is to collapse many moments in time into one frame. In other words, do long exposures. It can be extremely useful at removing textural detail that I don't need in the photo, as in the example below:

Removing textural detail by use of Long exposure

Fjallabak, Iceland

Image © Bruce Percy 2017

By removing any small currents in the water, I've removed any possibility of the eye being distracted and therefore drawn to it. Similarly the long exposure has reduced the chance of the sky having anything of distraction in it either. So my eye is allowed to go straight to the headland.

Using long exposures in this way can remove distractions and allow (in this case) areas of the picture to become 'wallpaper' - regions where your eye just floats over the surface. 'Wallpaper' is an integral component of most photographs: there are always going to be areas of the picture where you wish for the viewers eye to float freely without getting trapped or stuck.

By smoothening any textural details out of these regions of the frame, I can also allow the viewer to see the gradual tonal shifts that underpin the area. For instance, if you look at the water, the tones get darker as we move towards the bottom of the frame and the eye enjoys seeing smooth gradual shifts.

Similarly with the sky I've adopted the same approach, which is perhaps a point on its own: if you have clouds, do you need them? Often I'm wishing for skies with either complete cloud cover (for softer light all-round), or to reduce textural detail in the frame. I will deliberately go to certain places at certain times of the year because the skies are clear of clouds (Bolivia for instance) otherwise there is perhaps too much information or 'things' for the viewers eye to get stuck at. We're back to talking about tones and form. Too much form and we have too much distraction. So I'll often use a long shutter speed to smoothen out the clouds in the sky.

If you're a film shooter - which there is a good chance you might be in 2017, since I've begun to notice over the past few years that around 2 people in every group of 6 is a hybrid shooter (film and digital), then doing long exposures require the need to calculate reciprocity.

Just in case you don't know what reciprocity is, I'll explain. When shooting film, most folk think that the relationship between the shutter and aperture remain constant. They don't. As you get down to longer exposures, film loses it's sensitivity; and the relationship between the shutter speed and aperture begin to drift apart. Typically once you get past 4 seconds with Velvia. Which means that if you rely on your meter, you're going to underexpose your images. So you need to compensate.

I didn't use a long shutter speed here. It was a very calm evening and the only possible textural distraction would have been in the reflections of the mountains. I felt using a long shutter speed was a case of diminishing returns: not required. So rather than use long shutter speeds all the time to smoothen things down, get used to 'reading' your landscapes - watch them to see how dynamic they are.

It's very easy to get into the realm of long shutter speeds if you are shooting in low light or with some ND filters applied. With Velvia, if your meter tells you the exposure should be 4 seconds and beyond, then reciprocity needs to be applied.

Here is a table of corrected values:

4s becomes 5s

8s becomes 12s

16s becomes 28s

30s becomes 1 minutes 6s

1 minute becomes 2 minutes 30 seconds

2 minutes becomes 4 minutes, 50 seconds

And you shouldn't need to go beyond that, as the contrast will get too high and the colours too funky.

Either write them down, or better - remember them. I used to have them on a little laminated card for the first few years of shooting, but the corrections have now been memorised. That's one of the beauties of staying with a single film type for most of my photography career. The less variables I have to my 'process' the more second-nature things become.