What is perhaps not talked about so much is the act of living with current work that one is not so sure about. Probably because if you tell your audience that you’re unsure about the work, the audience may mirror that uncertainty. It’s common for people to lose interest in what you’re doing if you tell them it’s substandard.

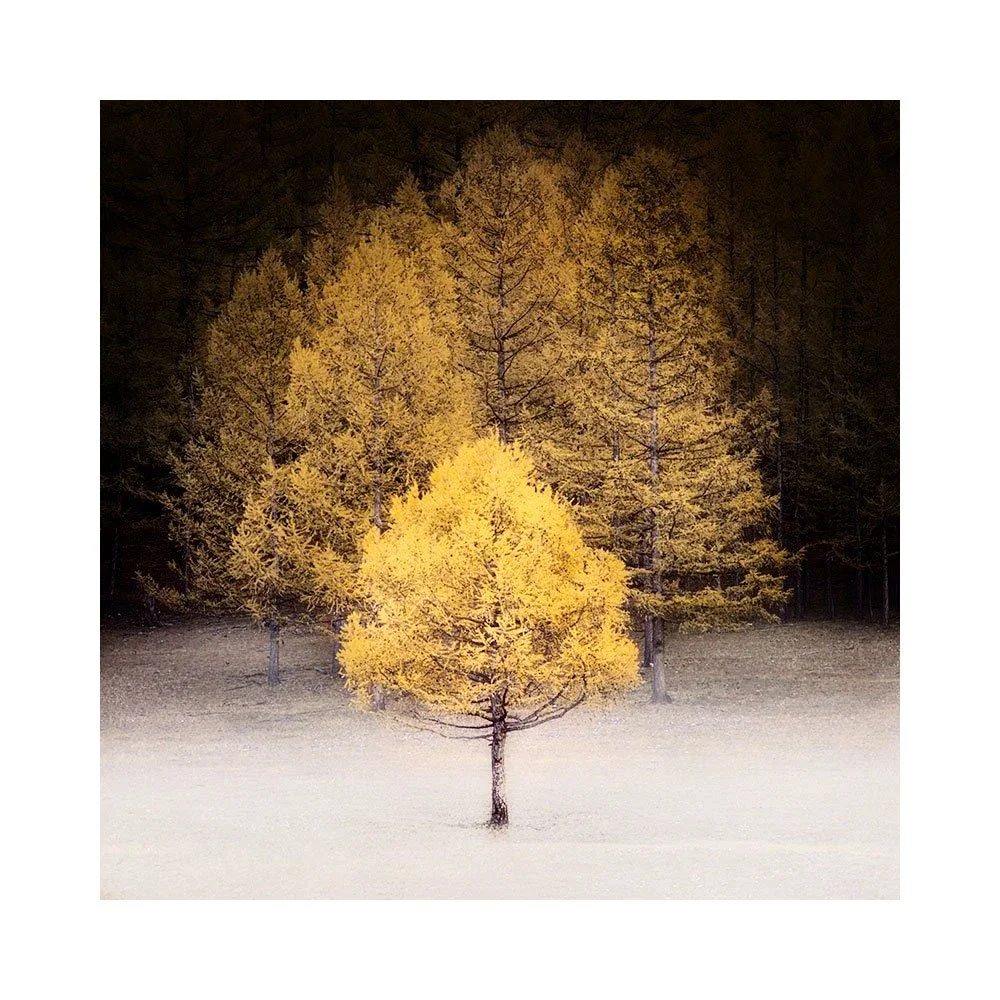

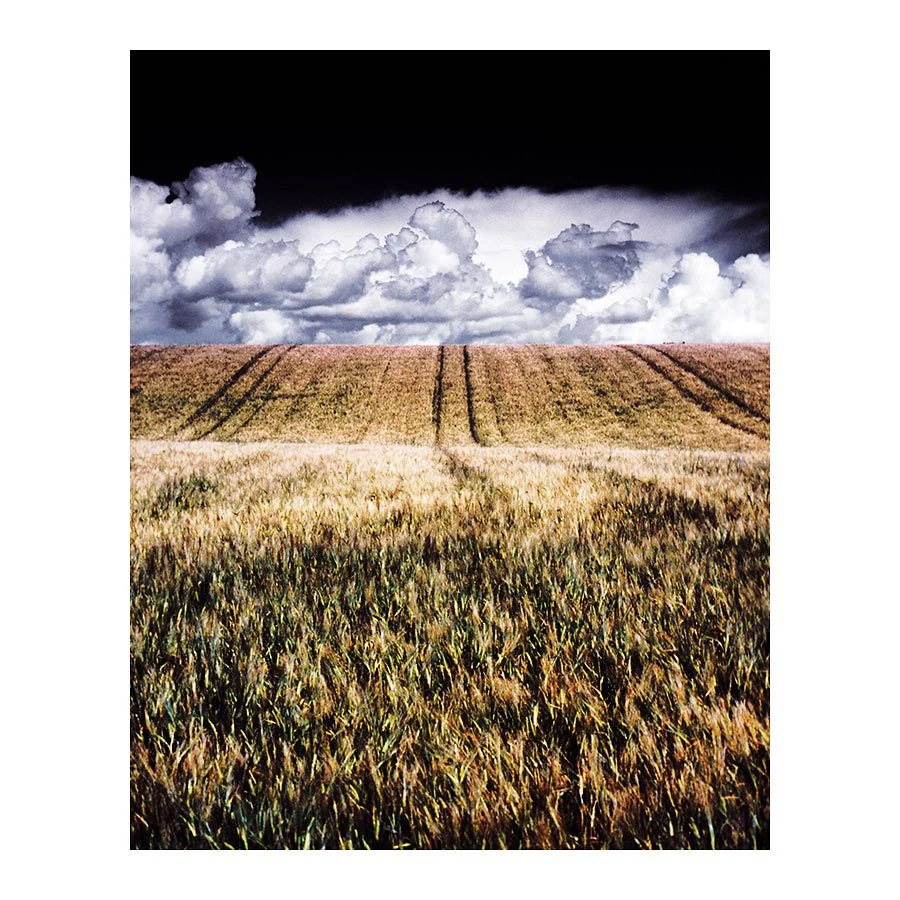

Last year, I felt I had optimal conditions on the Isle of Harris to make my dream portfolio of the place. We had a lot of fog during the first week, and a lot of snow in the second. I was sure I would come away with some really interesting images—enough to make a very good portfolio.

The problem was that I was never entirely happy with the portfolio I produced at the time, and I struggled with where to go with it. Some days I felt it was too light, and when I tried to put more depth into it, I felt it then suffered from being too stark, too hard.

The best approach I eventually settled on was to let it be and live with it for a while. This is really the point of this post.

Today, I’ve been reviewing the past year’s work. I feel I’ve now had sufficient distance to take the images as they are. I think I’ve managed to shake off any preconceived ideas or aspirations I had held. It was clear to me back then that the work didn’t meet what I had aspired to, and I now realise that this was getting in the way of seeing what the images actually offer.

Audiences tend to be one step behind the artist they’re following. When the artist is moving on, the audience often only recognises it after some time. You get rated on what you were, not what you are.

Sometimes an audience may resist new work because it isn’t “like the older, more familiar work.” I sometimes wonder if this is also true for the artist themselves. They, too, can be at odds with their own work. Perhaps the work is advancing, and they’re simply not up to speed with who they are now. I think this is possible.

We can be out of step with ourselves. Our perception of our ability or artistic voice doesn’t always match the reality of where we currently are.

Recognising that this can be the case is the first step in artistic mental health. Accepting it is the second. And perhaps being okay with the ebb and flow of your abilities is the final step.

Anyhow, I sometimes think we’re simply not ready to accept our current work. I’ve had work that I wasn’t sure about, only to find that it grows on me over time. Sometimes I’m pleasantly surprised by work I once thought was merely so-so. That’s just the nature of creating.

Learning to live with ourselves—our expectations of our work, and the reality of what it actually is—can be tough. You need to practise positive mental-health attitudes towards yourself and your art. Be kind to your creativity is something I’ve always believed in, and perhaps allowing your work—even when you’re uncertain of it—to have time to grow on you is part of that kindness.