Building relationships is key to everything we do in life. In the case of friendships and family, we have to spend time with them to let the relationship blossom and deepen. The same is true of landscapes. As we spend more time in certain places, the relationship deepens. We begin to understand them in ways that the casual observer does not. Similar to meeting people for brief moments although we get a rush of new impressions, the relationship is still too young to really know them. So too, with landscapes.

hrafntinnusker, Iceland

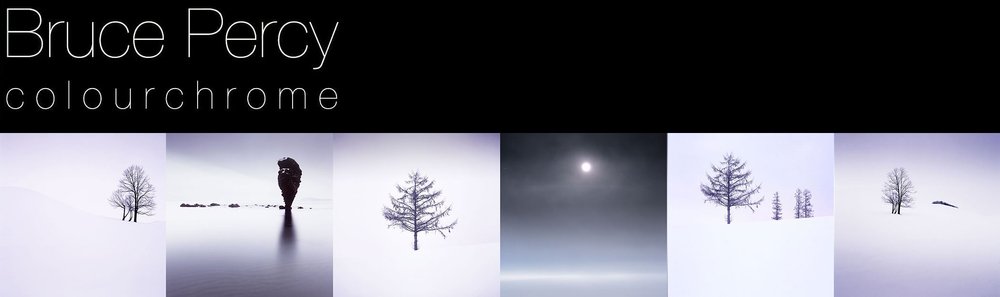

Image © Bruce Percy 2017

I'm lucky that over the past decade that I've been living my photographic-life, I've had the luxury of repeatedly visiting certain landscapes. They have become intimate, personal friends. Some I now know so well they are like old friends: I don't need to see them too often, but when I do encounter them, I know exactly where I am with them. Others are recent friends, I've known them for maybe a couple of years and I'm still learning about them.

We also define ourselves by whom we know. I think I define my photography by the relationships I have with certain landscapes. Iceland has been part of my photographic world for thirteen years, while Patagonia fourteen years. The Fjallabak landscape in the central highlands of Iceland is relatively recent as I have been spending time with it for around five years now. And then there is Hokkaido, a recent acquaintance of just over two years that I am still getting to know.

They have helped shape and define my photography, and my photography has contributed to who I am. So in a sense, these landscapes are part of me.

We should be choosy about whom we let into our lives. Invite those that are supportive and that you can support back, is my advice. Being around healthy attitudes and positive people is an ingredient for a happy life with room for you to grow. Similarly, choosing your landscapes wisely, by going for those that resonate with you and perhaps those that keep calling you back is vital, if you are to develop your own internal landscape.

hrafntinnusker, Iceland

Image © Bruce Percy 2017

The landscapes I work with have defined part of who I am. They have defined my signature. They illustrate not only what I resonate with, but also what appeals to my aesthetic. There is often a theme running through all of them. I do not just go anywhere. I am only interested in spending time with those landscapes where I know that I grow with each visit.

Choose your landscapes wisely and they will support you as a photographer. Work with those that resonate with you, because that is where any development in your photographic style will eventually occur.