I got asked recently whether there was a way to use the gradient tool in Photoshop in the same way the gradient tool works in Lightroom. The observation was that with Light room, you are able to reposition the start and end points of the gradient by dragging them, whereas with Photoshop you cannot do this - instead you have to redraw the gradient until you finally get it right. Each time you redraw the gradient, you overwrite the last effort.

It was a question I had not been asked before, but it led me to think about the pros and cons of using a gradient tool that allows precision re-adjustment (Lightroom) or one where you are forced to redraw it if the positioning isn’t right (Photoshop).

My preference is for the Photoshop way. I admit that since Photoshop’s way of drawing grads was the first way I learned, I may be biased because I’m simply used to working that way. But I think there is an important difference between the two methods.

Are you an Artist?

Painters in general don’t use precision tools to reposition their paint on the canvas. Indeed, I think that part of the artistic effort of painting is that you respond to how the brush strokes surface on the canvas as you brush. Painting is very much an emotional response between the hand and the eye. And indeed, I would suggest that sometimes painting a brush stroke a way that was not intended can be highly surprising and creative, leading you in directions you had not envisaged.

To me, that’s what the Photoshop gradient tool is like. You draw with it and wait to see what result it gives you. If you’re not happy, you re-draw until you get the right emotional response.

In my view, it’s about going with an emotional feeling and just applying the tool until it feels right. It’s more ‘creative flow’ than ‘analytical’.

Are you an architect?

Architects on the other hand, want to create work that is exacting. They need things to line up and the precision part of it is less ‘creative flow’ and more ‘analytical’.

That’s how Lightroom’s gradient tool is for me. It displays scaffolding around its start and end points so you can be precise and reposition the grad exactly where you want it to go.

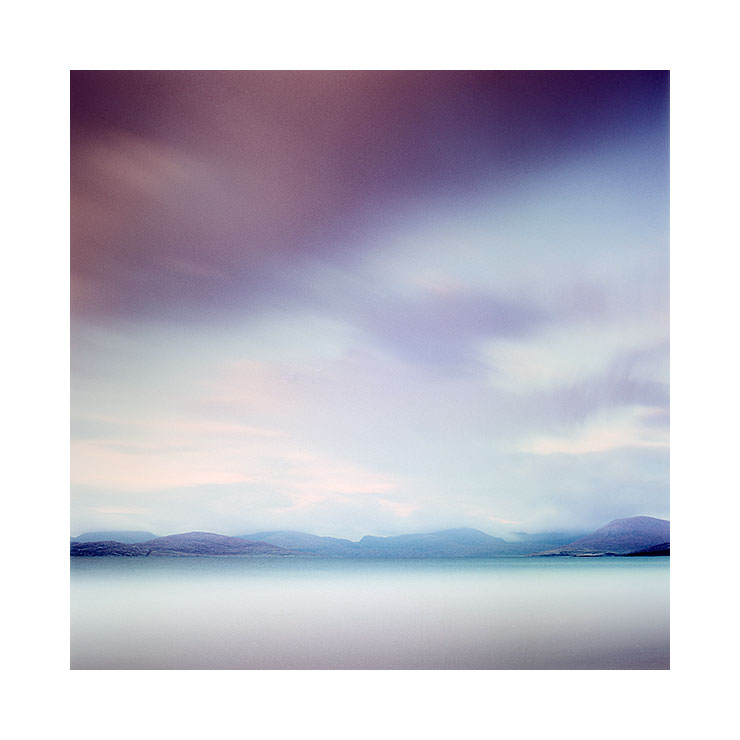

But I feel that by staring at the scaffolding - the start and end points, you’re no longer looking at the photo. An analogy I’d put forward is that you’re so busy driving the car that you’re not seeing the scenery.

So for me, I’d much rather work with the Photoshop gradient tool. Because each time I draw with it, I don’t really know exactly what I’ll get with it, and that can lead me in directions and results that I had not imagined. I also think that the act of drawing is much akin to painting, and less about being an architect. It’s about emotional engagement more than precision engineering.

If I had a choice

I would have both modes of operation available:

Grads that you just draw with your hand

Grads that you can reposition.

The first is artistic and emotional. The second is analytical and maybe the process is that we start with the first, and then perfect with the 2nd.

I love mistakes in my work. I love not knowing where things are going exactly. That to me, is the definition of what art is. It is not about control, nor is it about perfection. It is about feeling and emotion, and each time I draw or paint with brushes and gradients I get an emotional response immediately. So I’d personally prefer to work with Photoshop’s Gradient tool, than a tool I have to set the start and end points. There’s too much ‘context switching’ from ‘creative flow’ to ‘analysis’ with the later whereas the former just keeps you in the ‘creative flow’ mode.