Today I was asked by a participant if they should bring along copies of their previous work for review during one of my mentoring workshops here in Scotland.

Over the years that I have been teaching in a mentoring situation, I've found very little merit in looking over what someone did before spending time with me. Instead, what I find more valuable is to spend time with the participants on the workshop. I'm able to get a clearer picture of where they are technically and artistically, and more importantly who they are.

I would like to go into in detail today on this post for my reasons why I feel reviews of past work aren't of much value. I know this may go against the grain for some of you - particularly with USA clients as I hear bringing along portfolios for review is a common component of many workshops in the states. But if you can bear with me, I'd like to spell out my views on the value of critiquing work created *during* a workshop, rather than relying on work created elsewhere.

In general, I don't find looking over past work to have much value for the following reasons:

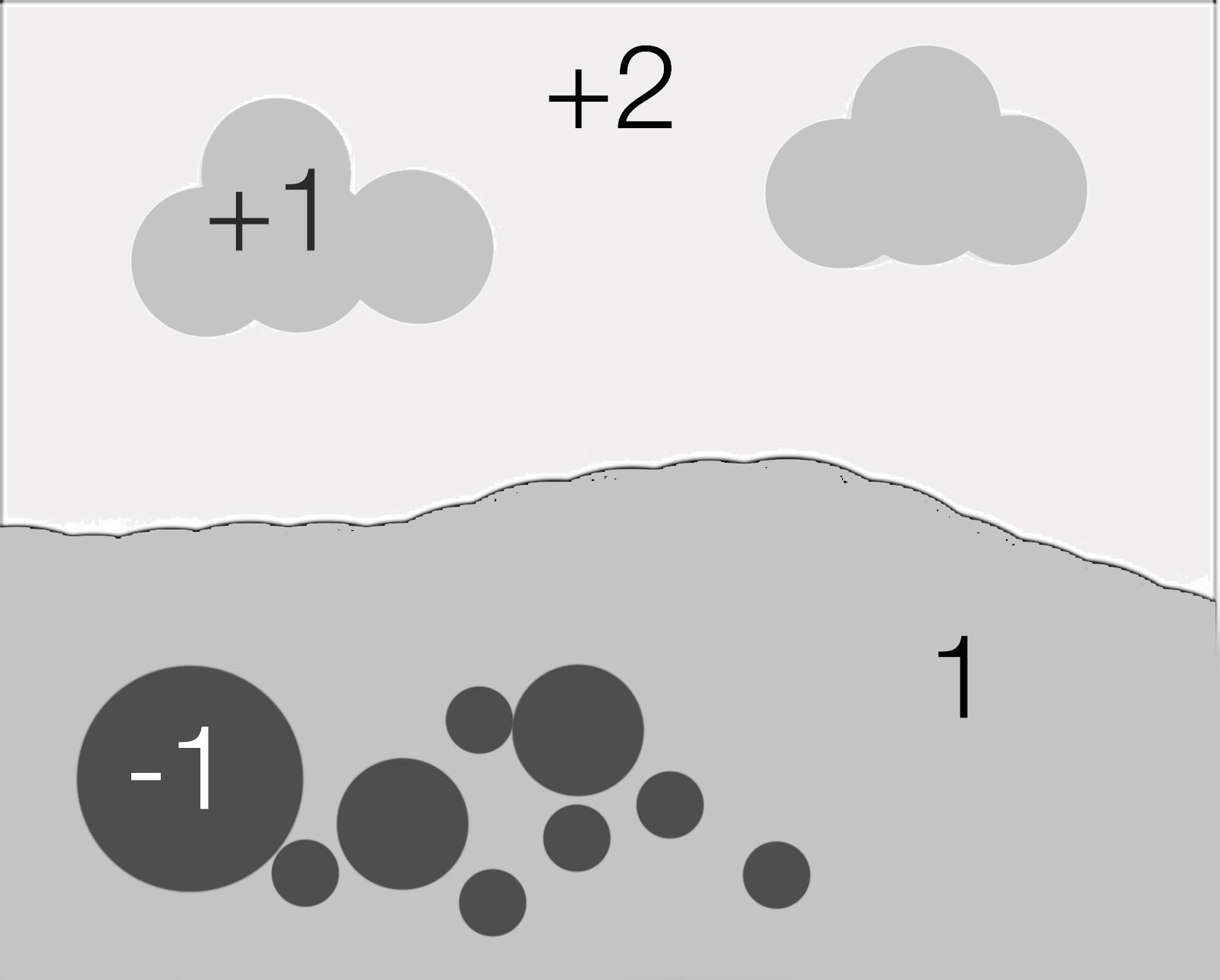

There is no audit trail

When I mean 'no audit trail', I mean that it is very hard to get an understanding of what limitations and conditions the images were made under. Why did the participant choose a certain composition and what obstacles did they encounter at the time? If something clashes in the landscape, I do not know if this was noticed at the time of capture but was chosen because it was the only way to make the shot, or if it was chosen because the participant did not notice the error at the time of capture.

Further to this, in the case of edited (post-processed) work, it is doubly difficult to give advice because the original unedited raw material is not available for comparison. It's important to see the journey the image made from capture to final edit and if the unedited work is available I can see what choices were made, or how different the final edit is from the original capture. But this is rarely provided.

Also...

Past images show no indication of current abilities

Indeed, it is often hard when looking at the finished work to get a sense of what the participants abilities were at the time of capture, and more importantly, where they are presently. It is not uncommon for me to be shown images that were made a year or several years previously.

It is however, possible for me to draw up a rudimentary idea of the participants current ability. But only to a point. It is very easy to see if the work is accomplished, but other than that, I am left with a lot of unanswered questions, such as:

1) Was the participant shown the composition or did they choose it themselves?

2) Did they understand the value of the quality of light they shot in, or again, were they shown it?

3) Are these images the best they've made over the past few years? and do they truly represent their current ability? What a participant may think of as important work to show me may not be. I am often surprised to find out that participants have shown me work I have very little to contribute towards, only to find out later there was other work they did not show me which may have provided more value as a critique session.

4) Have these images been reviewed and edited several times before by other workshop leaders? Is what I am seeing now, an amalgamation of other people's ideas? or is this an accurate view of the participants own ideas?

I really have no idea.

So I believe that looking at previous work is of little value. I don't know what choices were made and why they were made. Which leads me on to my next point;

I was not there, I do not know the limitations the participant was under

Giving composition advice of 'if you stood two feel to the left', is invalid because I wasn't there. There may have been a pool of alligators to the left, or something distracting that the participant managed to remove. I do not understand what limitations were placed upon the participant at the time of capture.

Which is vital to know, as I can gauge what they did and why they did it if I had been there to observe. And observing is a key ingredient of a good workshop leader.

Workshop leaders should be observers

My own view of my job is this:

1) To be able to watch and study my participants and notice how they approach their work

2) To understand how they react to failure

3) To understand how open they are to working with what they are given

4) to understand what their current level of ability is

Point 4 is perhaps the most important because I've had many people downrate themselves only for me to find out they are more competent than they let on. They have talents beyond the scope of any work they may show me from previous outings. On the more negative side, I've had some people talk up what they do and before they begin I'm given a very false idea that they are more accomplished than they turn out to be.

Ultimately, reviews really require an understanding of what motivated the participant, and this can only be drawn upon if I spend time with them in the landscape. Because during this time, I'm able to observe them and notice habits, limitations and aspects of their character that either lend or detract from them making great images.

The value of critiquing present work

Which leads me to why I think turning up at a workshop with a 'clean slate', and getting critiqued on the images you shoot during the workshop is of much better value:

The audit trail exists!

I get to see first-hand what you shot. I get to see the raw data on your memory card. I get a really good picture of what your level of ability is. All this is possible by looking at the images you shoot each day.

Images shot during the workshop show current abilities

I also get to see the most up-to-date impression of your current ability.

I'm able to observe participants and work with them on location

Being there allows me to walk through the process of setting up a shot with the participants, or by stepping in at the last point to see what it is they've set up and to give guidance on what I think can be improved or to point out problems or distractions that they may not have been aware of.

But most importantly, being on location with participants allows me to get more of a direct hands-on feel for what motivates them, and to discuss potential problems at the point of capture, rather than afterwards during the critique sessions when it may be too late.

I was there and I knew the limitations participants were under

Which is kind of similar to the previous point. Simply being there and understanding the weather conditions and physical limitations of a landscape can help me get a better understanding of what was driving the participant to make the images they made.

And lastly.....

I know the person behind the camera

This is perhaps the most important aspect of on-site critiques of current work: during the week I get to know the person behind the camera.

I am able to see how they approach failure, understand their process or notice their good/bad habits. I also get a really good understanding of how much they actually 'see' and what their visual awareness ability is like . Being able to notice these kinds of things about my participants is a skill I believe that all workshop teachers should have.

Being a workshop leader is really about tuning into what each participant is trying to do. There's a fair degree of anticipation involved in trying to work out what each participant is doing and understanding their limitations. It's also about encouraging the participant and trying to be as objective about their work while remaining encouraging.

This can only happen if I am on-site with them, as I get to see them working in the field. It does not happen by reviewing images that were created elsewhere, under circumstances that I am not aware of, or motivations that are now long forgotten or past.