I've just found 4 remaining copies of my Iceland 'Deluxe' edition, which I had thought had sold out a few years ago. This is the version of the book that comes with three prints of the beach at Jokulsarlon - so they can be framed as a tryptich. Perhaps a nice christmas present for somebody (perhaps yourself? !) :-)

Deluxe edition comes with 3 prints that can be framed as a tryptych.

Preface by Ragnar Axelsson

Release Date: 1 November 2012

ISBN 978-0-9569561-1-8

Hardback, Cloth, 30cm x 28cm.

64 pages with 45 colour plates.

First edition. Limited to 1,000 copies.

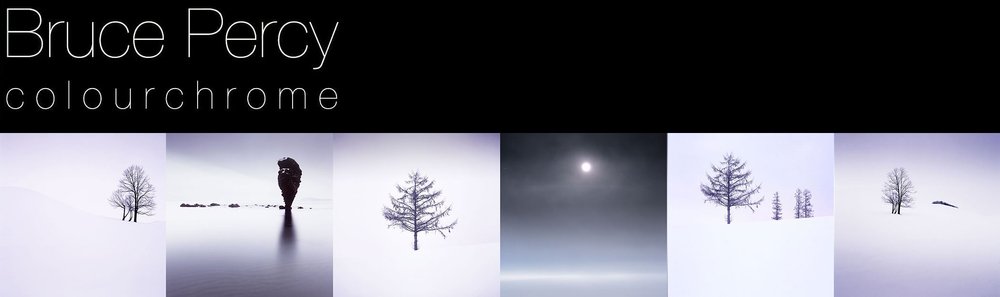

This book encapsulates all of Bruce's nocturnal photographs of Iceland made between 2004 and 2012.

The book has a strong nocturnal theme. Mainly a monograph in nature, it is interspersed with entries from Bruce's journal with thoughts that deal with his experiences of shooting the icelandic landscape in subdued light.

The book can be seen as a photographic day, shot over many years with the opening presenting us with late evening shots. As the book progresses, we move into the small hours of the summer night, where there is no night at all. The book concludes with winter shots made during the fleeting sunrise and sunset of the shortest days of the year.

This book comes in four variations:

- Standard Edition

- Signed Edition with Jokulsarlon Ice Lagoon Print (60 copies).

- Signed Edition with Selfoss Waterfall Print (60 copies).

- Deluxe Edition (book with 3 special Ice lagoon prints, 50 copies).

The prints are 7" x 9" in size, printed on A4 Museo Silver Rag Fine Art Photo Paper.

The have been printed signed and numbered by Bruce.